Does Verizon have access to rich user data? Undeniably. Will Verizon successfully capitalize on that opportunity? Questionable.

Does Verizon have access to rich user data? Undeniably. Will Verizon successfully capitalize on that opportunity? Questionable.

After all, Verizon’s user data is only as valuable as its data practices.

Verizon could certainly benefit in the wake of an acquisition spree that somewhat resembled a line of falling dominos – AOL into Verizon, Millennial Media into AOL. Blend Verizon’s deterministic data set with Millennial’s roughly 700 million unique device IDs and the potential result is an offering arguably competitive with anything Facebook or Google provides.

“What Millennial used to view as multiple different users, they can now see as a single device – and, hence, single user – moving across multiple mobile apps and properties,” said Mike Driscoll, CEO and founder of Metamarkets. “Layer in Verizon’s subscriber information and you have a data set for programmatic marketers that rivals, or even exceeds, that of Facebook in terms of richness.”

But Verizon will have to tread lightly on the privacy and data collection front if that story is going to have a happy ending – aka, not become the sequel to the zombie cookie episode of this past January in which certain Verizon partners took advantage of the company’s header to resurrect opted-out cookies.

About a week after Verizon battled the bad press that resulted from its seemingly unkillable supercookie, the carrier announced that it would in fact give its users the option to opt out of its persistent tracking mechanism. Previously, although Verizon customers could say no to seeing targeted advertising, they didn’t have the ability to nix tracking altogether.

That said, there is evidence Verizon has some work to do if it wants to successfully take advantage of its user data for advertising purposes.

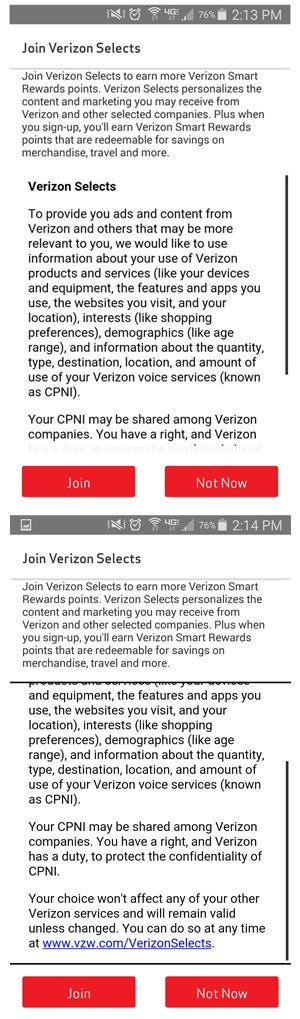

Consider the push message (see right) received by an AdExchanger staffer several weeks ago, which prompted her to join the Verizon Selects program. The notification, which could only be eliminated by first opening it, is a salient example of the sort of heavy-handedness that won’t fly in a world where consumers are, as Forrester VP and principal analyst Thomas Husson put it, increasingly “aware of the ‘hidden harvesting’ of their mobile data.”

Consider the push message (see right) received by an AdExchanger staffer several weeks ago, which prompted her to join the Verizon Selects program. The notification, which could only be eliminated by first opening it, is a salient example of the sort of heavy-handedness that won’t fly in a world where consumers are, as Forrester VP and principal analyst Thomas Husson put it, increasingly “aware of the ‘hidden harvesting’ of their mobile data.”

It’s noteworthy that the text-heavy push message in question doesn’t give the recipient an option to opt out. The only two choices are “Join” or “Not now.”

A bit of backstory: In 2012, Verizon launched its addressable advertising unit, Precision Market Insights, followed shortly by Verizon Selects, a program that encourages subscribers to opt in to receive targeted ads based on their web browsing, mobile app usage, interest data, location and the like.

When Verizon launched its Smart Rewards program in July 2014, opting into Selects became a prerequisite of joining.

While the transparency around data collection in the Selects push notification is laudatory – Verizon ostensibly has access to a vast array of customer data, everything from site visits to physical address, without even asking – the subtext is: You have no choice.

“It’s a bit like asking someone to go on a date and the only answers you’re allowed to give are ‘Yes’ or ‘Not tonight,’” Driscoll quipped.

It’s unclear how many users are seeing similar popups, but the hamfistedness of this example is symptomatic of a historical trend among the carriers – a seeming inability to activate the opportunities on their doorstep.

“It’s almost a redux of when mobile phones first came on the scene and all the carriers thought, ‘Wow, we’re in a position to monetize apps like ringtones and map apps on our devices,’” one source told AdExchanger. “But look at how woefully they executed on delivering value on their own platform in the world of apps. It turned into crapware, and it wasn’t until Apple came out with the iPhone that the nasty walled gardens of terrible content and apps the carriers had built ultimately crumbled.”

Verizon’s success around advertising will be determined, at least in part, by the way in which it approaches consumer privacy, Husson said.

“Facebook’s or Google’s business model is based on advertising, but that is because users don’t pay them anything,” said Husson. “But it’s different for a carrier. You’re paying them for a service and because of that, you expect something different. What’s at stake here at the end of the day is the customer relationship.”