Banning password sharing is No. 1 on Netflix right now.

Netflix reported a huge jump in subscribers over the summer – six million new sign-ups, compared with 1.5 million during the prior quarter – which it credits in large part to its anti-account-sharing measures. Weeks later, Disney announced that it, too, has plans to implement anti-password-sharing tactics.

Although Netflix is keen to attract any new subscribers, its goal here is to encourage new subs to sign up with ads. People who create their own accounts after getting kicked off of a shared one are likely to consider the cheapest – aka ad-supported – option.

The strategy appears to be working.

Nearly one quarter (23%) of new Netflix subscribers in July signed up with ads, up from 19% in June.

Other streaming services, including Disney+, are “definitely taking notice,” Teresa Doyle Kovich, a principal consultant at data consultancy DAS42, tells me.

But despite their interest, other major streaming services don’t (yet) have a way of implementing anti-account sharing on their platforms.

The strategy is also a risky one: It’s very difficult to enforce, and the timing needs to be just right.

Whac-a-mooch

Platforms can easily detect when a user profile is accessing an account from a different IP address than the one associated with the account owner. That’s how Netflix has been able to kick so many individual users off of shared accounts.

But it’s more difficult to spot account sharing when people who live in different households are accessing an account through the same user profile. It certainly explains why I still haven’t been kicked off of my aunt’s account despite living nearly an hour away from her: I chose to use her profile rather than create my own.

Services can also analyze differences in viewing patterns within a profile. For example, Netflix may notice that the same user is watching “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” in one location and “Gilmore Girls” several hours later from a totally different location.

Still, it’s not a guarantee that those differing consumption behaviors represent two different viewers. People often choose to binge certain shows at home but watch something different when they’re traveling or taking a break at work.

One of the worst things a service can do is block a user who’s legitimately accessing a service from an account that they are, in fact, paying for, Kovich says.

So, in the case of shared user profiles, it’s better to let suspected account-sharing slide than risk the customer backlash (and possible bad press) that would result from cracking down in error and revoking the wrong person’s account privileges.

(Guess the best way to avoid getting kicked off of a shared account is to avoid creating your own profile on that account, at least until Netflix’s detection system gets more sophisticated.)

Risks and rewards

Still, despite the potential benefits, enforcing anti-account sharing doesn’t make sense for every streaming service. Companies must weigh the risks.

And for newer services that are still in the early stages of building up market share, encouraging subscribers to share their accounts may actually work as a promotional strategy to get more viewers on a platform, Kovich says.

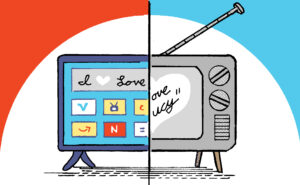

Remember when Netflix tweeted that “Love is sharing a password”?

But streaming services need to focus on scaling subscriber growth before they can afford to risk churn in an effort to achieve profitability.

When done right, however, anti-password-sharing efforts can bring in new subscribers and, as a result, more ad revenue. When done prematurely or tactlessly, though, it could knock you out of the game.

Are you enjoying this newsletter? Let me know what you think. Hit me up at [email protected].