“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Tom Triscari, CEO of Labmatik.

Growth in ad blocking has been the topic du jour in the advertising trade press and it is rightly fueling fears across marketers and publishers alike.

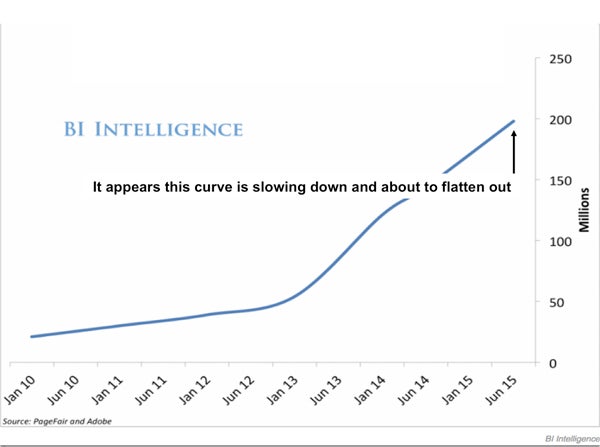

But based on a recent Business Insider (BI) chart, I estimate that desktop ad-blocking growth could peter out at around 250 million users by 2025. That is around 7% of the world’s current 3.4 billion internet users, and less than 5% of the 5.5 billion forecasted users by 2025.

This slowing growth rate might not be obvious at first, but after giving BI’s data a closer look it appears that ad-blocking growth has passed an inflection point. If so, this means period-over-period growth is no longer happening at an increasing rate but at a decreasing rate.

Chart A: B.I. Intelligence – Desktop Ad-Blocker Users (Global)

To better prove this observation, I created a simplified diffusion curve forecast to study when ad blocking will reach maturity.

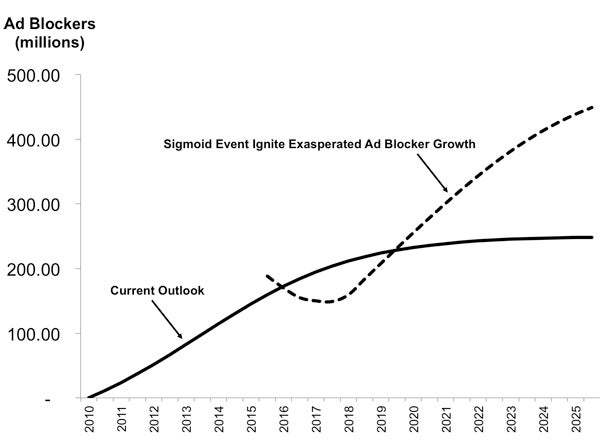

Chart B: Growth Curve Forecast Model

The General Nature Of Diffusion Curves

If BI’s numbers are correct, then advertisers and publishers may not need to worry too much about a potential ad blocker China Syndrome. While that might alleviate some worry, the more important matter is the actual composition of the 5% of internet users who block ads and how meaningful it may or may not be.

For example, if ad block users are mostly composed of consumers with low purchasing power, then it may not matter if ads actually reach these folks. If the opposite is true, then the resulting permanent loss of exposure to valuable customers will likely have some impact on advertisers and publishers, but probably not lead to a total meltdown. The most probable outcome in this case would be a tightened supply shift resulting in minor upward price pressure if any at all. Not a big deal, right?

What should be more important than any financial impact is the wake-up call for both sides of the trade to change behaviors by implementing much more governance over their ad-buying operations. Such improvements are particularly paramount at a time when digital is eating traditional advertising and programmatic is munching away at digital. If the end game of programmatic results in significant ad blocking, then the entire industry will have missed a massive opportunity to create consumer utility rather than destroy it.

And while data and machines are increasingly used to automate and deepen governance, it is still human decision-makers who set the dials, own diligence and take responsibility for consumer experiences. If not, ad- blocking growth could very likely experience a “sigmoid” moment, which would mean both sides of the trade, including agencies in the middle who possess nearly all the bargaining power, have failed to take notice and make appropriate changes with consumer experience as their top priority.

Sigmoid Events And Network Effects

Sigmoid events happen when a diffusion curve – also known as an S-curve – starts to flatten out and appears to have plateaued into steady-state maturity, but then reignites into a subsequent growth cycle. It is easiest to think of this effect as a new S-curve growing out of an old one.

Chart C: Exasperated Growth

When observing such events, the first thing to consider is how impactful word-of-mouth effects might be with respect to powering the curve’s growth. The second thing to consider is whether it gets easier or more difficult to reach maturity as the curve approaches maturity. If these so-called “network effects” are intense, then ad-blocker growth will take an even faster ride up to maturity.

Michael Rosenwald, a Washington Post staff writer who covers the intersection of tech, business and culture, gives an excellent example of how network effects are likely playing a big role with ad blocking:

“Not long ago, I moused over to AdblockPlus.org, clicked on a green button that said, ‘Install for Safari,’ and fewer than 10 seconds later, ads had vanished,” he wrote. “All of them. Goodbye iPad ad that unfurled down my screen. Goodbye blinking mattress ads. Goodbye car ad following me from site to site. This immediately became web surfing nirvana: Pages loaded faster, my browser stopped randomly crashing, my whole computer ran better. The Adblocker Plus plugin even told me how many ads I’ve dodged in the last couple of months: more than 35,000 and counting.”

Rosenwald goes on to explain his own experience with network effects: “I am not alone in my love for ad blocking. Every friend I tell about it thanks me with extreme enthusiasm, as if I’d just changed their flat tire.”

Avoiding Ad Blocker China Syndrome By Changing The Compensation Model

What’s at stake if supply chain participants don’t heed what we already know? In a recent interview, Essence co-founder and chief product officer Andrew Shebbeare rightly hinted that ad blocking is more than symptomatic, and the entire supply chain should take note with impactful and immediate action.

There is a lot at stake for a supply chain competing for a share of the $50 billion programmatic market and $100 billion-plus overall display, video and social market. And the key consideration in the chain of advertisers, big agency bargaining power, ad tech and publishers should be focused on one essential fact: After the advertiser writes the first check in the chain, nearly everything that comes afterward is supported by percentage of media spend.

Unfortunately, this all-too-common incentive lurks in every conversation and deal along the way. It’s an overarching pricing model that invites more ads because more ads supposedly equal more money. Advertisers end up with more unverified reach, unoptimized frequency capping and hypertargeting, which only seems to result in more annoyed users who don’t care or would buy the advertised product anyway. The result of this broken incentive is exactly what too many consumers are rejecting.

That said, the direct response ad bonanza is not entirely to blame. Think about all those nonprogrammatic, manually bought and poorly targeted “premium” takeovers, sponsorships and roadblocks that suck up millions of hours of low-value and high-margin manual labor (sometimes with rebates) and pump out even more ads.

And what about creative? As the creatives seek more awards and avoid adopting data like a trip to the dentist, consumers are rejecting their artistic interpretation of usefulness and ignoring messages that have no meaning. Any which way one stacks up the typical ad-serving pyramid seems to amount to more ads in the wrong moment and to the wrong persona with useless messages. Such a negative consumer response begs the question: Is all this brilliant ad tech and data being used to accomplish the right thing?

Three Obvious Solution Themes To Consider

If consumers are putting their hands up and screaming stop, the supply chain should be hearing them loud and clear. Listen before it is too late. Treat the disease, not just the symptoms.

For example, the first spoonful of medicine would include innovative, performance-based and data-driven incentives everywhere possible. Secondly, any and all effort to bring decision power back to the edges of the market where it belongs will make improved deal structures more viable and sticky. And the more advertisers and publishers find ways to work directly with each other and share the surplus value from direct dealings, the more likely their ads will be accepted as a useful part of the consumption process.

Lastly, the comfort of conventional media buying routines must continuously find ways to keep pace with unstoppable technological change. If not, the art and science of what modern marketing can offer to consumers will be greatly diminished and consumers will increasingly lean into technologies that lock brands out of their lives.

Follow Tom Triscari (@triscari) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.

Methodology Notes

Step 1: Calculate declining period-over-period growth rates using Business Insider plot points

Step 2: Approximate the declining exponential growth rate curve and forecast out a few periods to “fit” the maximum at maturity

Step 3: Fit curve in Step 2 to a Gompertz curve formula

Step 4: Fit Gompertz curve data to a Bass Model to separate out word-of-mouth viral factor from marketing influence