“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Amihai Ulman, founder and chief operating officer at Mass Exchange.

Markets and exchanges are now an everyday part of life in the media industry. Like all businesses, they seek to maximize value for customers and create the best possible incentive for buyers and sellers to participate. Since exchanges and markets are two-sided business models that bring buyers and sellers together in transactions, they must incentivize both sides to come to the table to the greatest degree.

In other words, markets and exchanges succeed when the opportunity to transact is maximized for both sides. This happens when markets are as liquid as possible. Unfortunately, today’s media markets and exchanges are just the opposite, which leaves buyers and sellers playing a guessing game.

The most visible symptoms in this illiquid market are massive volatility in several areas, including the second price, across all platforms, in open and private exchanges and the supply in open-market inventory. In financial markets, a 5% or greater spread between bids and what is asked is a sign of illiquidity. In media exchanges, the bid/paid spread averages 50%.

For sellers, this means that price floors are not effective in creating bid tension, which hurts aggregate revenue and has driven the recent shift to private markets. For buyers, supply is sporadic and unreliable as higher priority environments, such as guaranteed and private markets, intermittently siphon off supply, which increases price volatility even more.

The price volatility and lack of reliable supply make it nearly impossible to understand what the market thinks any impression is worth. We’re all flying blind. While there are market models that solve for these problems, none of the major players use them.

One Market, One Buyer

Currently, each bidder in an impression auction is likely bidding on a different set of attributes with a different ROI forecast. There are negative economic side effects when impressions are put into auctions designed for perfectly substitutable goods. In reality, each bidder is in their own micro-market with the publisher. A market with one buyer is not liquid, even if combined with many other buyers in a single auction.

When Google introduced a one-sided auction for search, it was, and still is, the right auction structure for that type of media. If all you know about an impression is the search string, such as “Hawaii flights,” all searches are equal. But when that market model was introduced to display media and used beyond bottom-of-the-barrel inventory, funky stuff started happening.

In the current auction models, buyers have no idea at what price sellers would be willing to sell. Sellers have no idea what an impression is worth. The auction model is designed to figure that out. But does the market model make sense if buyers and sellers already knew what an impression is worth before sale? Not always.

Illiquidity

While many refer to the opportunity to transact or the availability of impressions in a market as liquidity, like all things related to media trading, there is a subtlety when talking about the opportunity to buy actual impressions. The classic definition of liquidity is something that can be sold rapidly, with minimal loss of value and a continuous supply of willing buyers and sellers.

In a real-time delivery market, such as classic RTB and private markets, there is clearly a lot of speed, but what about the loss of value part? Selling an impression for some amount of money is better than nothing, but if the sale drives down the price of future transactions, value has been lost even if the sale generated revenue.

For example, airline seats, like impressions, yield nothing if left empty. But if a plane is half full, you couldn’t buy that seat for $10 at the airport counter and there would be no second- or first-price auction to determine the price of that seat. That would teach airline customers that seats could be bought very cheaply, at the last minute, which would drive incremental revenue and sell seats quickly but at a loss in the value of future sales. Eventually, customers would expect to pay less and would wait until the last minute to buy cheap seats.

A market is liquid if assets can be rapidly sold with little impact on value. The precipitous decline of media prices since the introduction of RTB and private markets, regardless of the number of bids, indicates the market has little liquidity.

A Willing Seller?

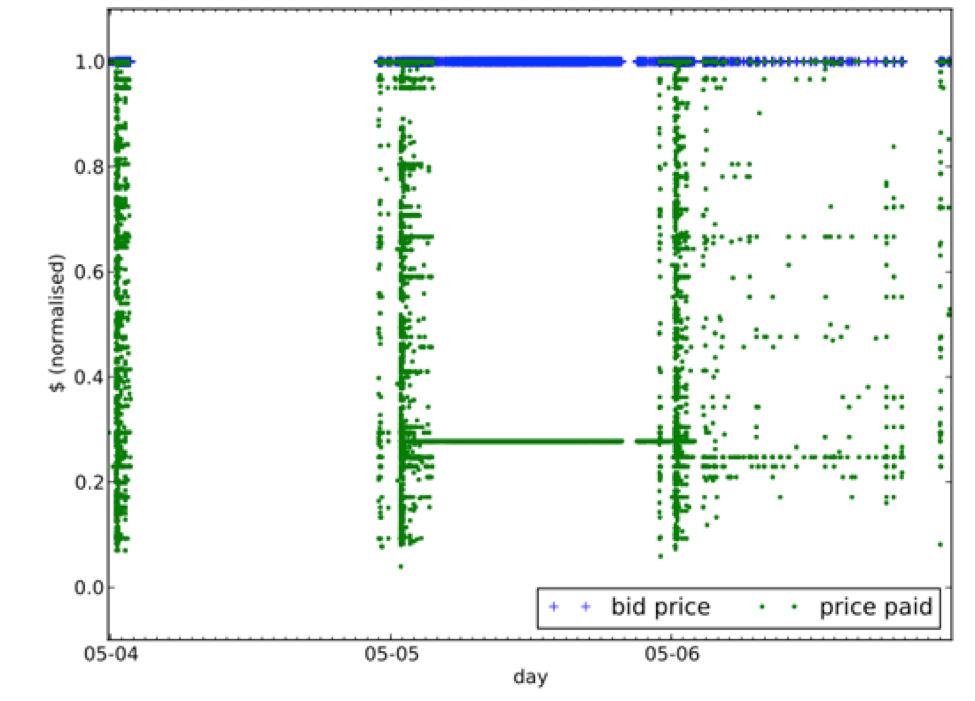

A 2013 study by Yuan, Wang and Zhao contains a visualization of auction liquidity by mapping bid price and price paid from 12,965,119 auctions, 50 placements and 16 websites of different categories.

In each auction the spread between the bid and price paid is the same as the gap between the first and second price. The spread is used to measure liquidity. This data indicates that the impression auction bid/paid spread average about 50%. In most financial markets, the bid/ask spread is less than 1%, while anything greater than 5% is considered illiquid.

That may sound like heresy to many media professionals familiar with ad tech. In reality, the essential characteristic of a liquid market is that there are always ready and willing buyers and sellers.

In real-time markets, sellers do not know if there are willing buyers until they offer the impression for sale. Sellers can guess what buyers may be willing to pay based on historical data, but there are no buy orders in the market for them to act against. For buyers, the lack of a “buy it now” price, with only price floors, means they don’t actually know if there is a willing seller.

All of this carries big economic implications, including the fragmentation of display media into billions of individual and illiquid micro-markets. The historic decline in publishers’ pricing power since the introduction of real-time markets has been driven by the creation of illiquid markets that have the illusion of liquidity, not the oft-repeated industry myth of infinite inventory.

Follow Mass Exchange (@MassExchange) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.