“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Jalal Nasir, CEO at Pixalate.

Life as a publisher used to be pretty straightforward. You simply sold your best inventory at the highest CPM your sales team could get, and whatever was left over was filled in with remnant ads. Aside from someone making sure to avoid channel conflict, nobody paid much attention to what we now call RTB.

Flash forward to today. RTB digital display advertising now accounts for 22% of all display ad spending. Last year, RTB grew at 76.5%, and by 2018, RTB is expected to account for one-third of all display ad spending, or $12 billion.*

And yet, not all players in the RTB ad ecosystem benefit from this growth. Publishers have it worst of all because price opacity prevents them from knowing the true value of their inventory. It’s estimated that, on average, bid clear prices for exchange-traded display ads are about 25% below high bids. As a consequence, publishers set artificially low floor prices. They’re losing money and, one could argue, are caught in a downward spiral.

And yet, not all players in the RTB ad ecosystem benefit from this growth. Publishers have it worst of all because price opacity prevents them from knowing the true value of their inventory. It’s estimated that, on average, bid clear prices for exchange-traded display ads are about 25% below high bids. As a consequence, publishers set artificially low floor prices. They’re losing money and, one could argue, are caught in a downward spiral.

How could this be happening?

Second-Price Auction Mechanics

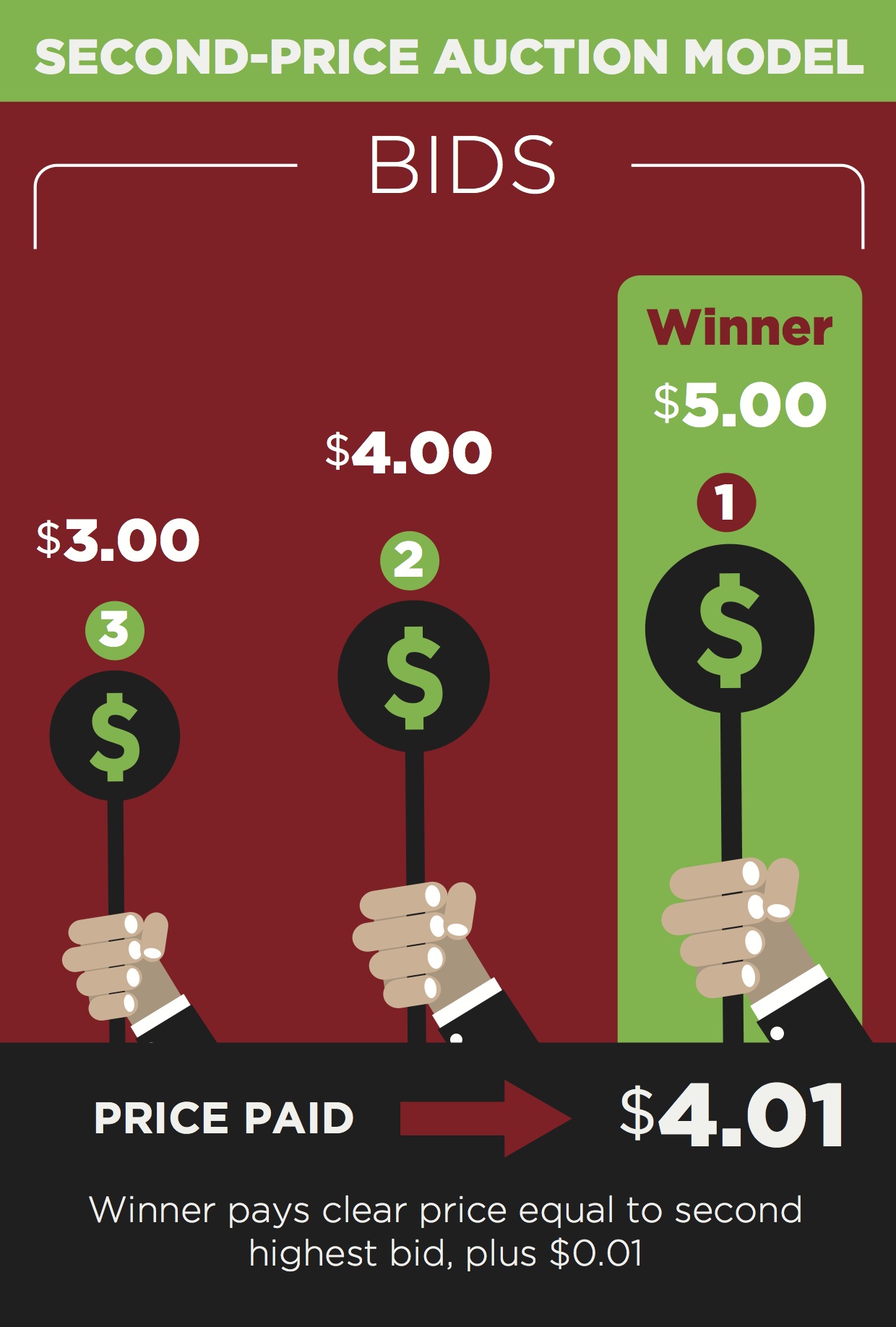

The majority of RTB inventory is transacted through exchanges that use second-price auctions. They work like this: Multiple buyers bid on an available impression. Bids are analyzed in real time by the exchange. The high bidder wins the auction. The winner pays a clear price equal to the second-highest bid, plus 1 cent.

Since the high bid is not the clear price, publishers don’t know the true value of their RTB inventory, and, by extension, don’t know how to price it. There is typically very little information made available to them by their supply partners. The price data they do get only includes the clear price for the ads, which does not represent the true value of the inventory. For example, if the high bid for an ad was $5 and the second-highest bid was $4, then the winning bidder only pays $4.01. This model may work well for other auction platforms, such as eBay, where consumers bid on unique or hard-to-find items. It, however, is not well suited to purchasing commodity items, where substitutes are readily available.

What makes this problem worse is diminishing bid density. Many advertisers now work with demand-side platforms, which aggregate multiple buyers’ bids into a single bid. There may be hundreds, or thousands, of advertisers bidding on the same inventory, but in the exchange, they appear far fewer in number. Lower bid density drives down pricing because there’s less competition for the same inventory. Defenders of second-price auctions argue that, over time, market dynamics will correct these problems and ultimately provide the best price for publishers’ inventory. Unfortunately, the time horizon required for this correction to occur is well beyond any of our life spans.

Not a New Problem

Historically, other markets have dealt with similar price opacity. In some cases, technology has been developed that has brought a great deal of transparency. Until Zillow came along, for example, there was no easy way for consumers to understand property values in real time. Sellers had limited price data available to them. Only licensed real estate professionals, with access to MLS data, could assess property values. Similarly, Kelley Blue Book started out as an annual automobile pricing guide. While helpful, it was a blunt instrument compared to websites like kbb.com, which is today’s Kelley Blue Book, and TrueCar.

The introduction of transparency into these previously opaque markets has increased confidence among market participants and created more overall transaction velocity. The real estate and automotive sectors have experienced healthy growth over the last few years. And while both markets are still recovering from the economic turmoil that started in 2008, it’s difficult to imagine that transparency has not been a critical accelerator of growth.

This same type of transparency must be brought to the exchange-traded display media ecosystem. Once market participants have a complete and accurate picture of price data, they will undoubtedly be more efficient, profitable and able to allocate more inventory to RTB.

But it’s unlikely that the major exchanges will move away from second-price auctions. It’s also unlikely that DSPs will go away anytime soon. So in the meantime, publishers must change the way they behave. They must invest in people and technology that can help them make smarter pricing decisions, which will ultimately lead to higher revenue and better profitability.

Follow Jalal Nasir (@jalalnasir), Pixalate (@PixalateInc) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.