“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Marcus Pratt, vice president of insights and technology at Mediasmith.

Measured in digital years, the banner ad may be approaching old age. Is it time for retirement?

Wired placed the first banner ad in October 1994, so the banner is now approaching its 20th birthday. A lot has changed since then when the web was still a novelty, Internet penetration was low and those who could get online were lucky to do so at a blazing 56k, tying up a phone line for the privilege. Now the US Internet population approaches 90%, high-speed access can be found in any Starbucks and banner ads are routinely served at 30,000 feet.

Despite the massive growth of digital media, the banner ad itself still looks strikingly similar to the early versions of the ’90s. To be fair, animations have (mostly) evolved past the Geocities era, a host of rich media executions provide multiple engagement options and banners sometimes expand beyond their borders.

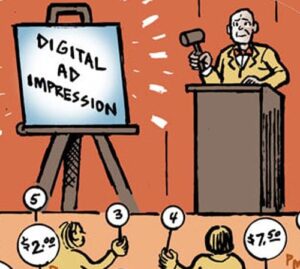

But RTB media, which represents the fastest growth within display, consists almost entirely of what the industry has deemed “standard banners.” These standard banners can be static or animated, and are typically Flash or image files. At their core these standard banners bear striking similarity to their ancestors: a rectangular shape separated from the page “content” while bearing little relevance to the rest of the page.

The banner has grown up since ’94, but it may not have evolved enough to stay relevant on today’s web. Over the years, many have questioned whether the death of the banner ad was imminent, yet the banner has continued to flourish. The banner ad faces several key threats in 2014.

Nobody Likes Them

Many forms of advertising receive their share of negative feedback from consumers, but the banner is a source of frequent derision among those in the advertising industry. Rarely do a creative director’s eyes light up over the possibility of putting their idea into a standard banner ad. Many creative agencies do not develop banner ads, focusing instead on creating brand experiences, apps, websites and other collateral. Even those on the media side have few positive words to say about the banner ad.

Attend just about any digital media conference and the key themes around banners are mostly negative: Almost no one clicks on them, half go unseen and a shocking amount are fraudulently served to robots instead of people. For a variety of reasons, display is simply not growing as fast as it once was, as Magna Global noted in an April report: “Traditional banner display campaigns on desktop Internet are now a mature format, barely growing (+3%) in 2013.”

AdExchanger Daily

Get our editors’ roundup delivered to your inbox every weekday.

Daily Roundup

Forget Mobile

If the standard desktop banner ad does little to excite creative teams, ask them about mobile banner ads. Mobile can certainly be part of an effective media strategy, but just 14% of mobile time spent is with a web browser, the original home of the display banner. Certainly many mobile apps offer banner advertising, but the effectiveness of these formats is largely unproven; problems with measurement, “fat finger” clicks and user irritation are common. Because of these challenges, many popular apps use other ad formats. About 17% of time spent on mobile devices is with Facebook or Instagram, neither of which offers banner advertising.

Social And Native

The popularity of social media extends beyond mobile. None of today’s popular social platforms support standard banner ad formats, which seems unlikely to change any time soon. When platforms like Twitter and Pinterest began to experiment with advertising, the ad units more closely resembled organic posts than display banners. These types of in-feed or native ad units are not limited to social media, with more mainstream publishers offering native advertising over the past year.

This trend is exacerbated on mobile devices; when limited screen real estate forces publishers to pick an ad format, they increasingly choose native.

“We believe in-stream native ads are the future of mobile,” Chad Gallagher, AOL’s director of mobile, summed up nicely.

Better Attribution

For years, many marketers have optimized display media on a “last-touch” basis, giving credit to the last banner a consumer “sees” before conversion, which could be a purchase, site visit or increase in brand awareness. Alternately, some marketers apply credit only to users who click on a banner prior to a conversion event. While the click-based approach can underattribute the impact of display, the last-touch approach makes many display tactics appear highly effective but reported results often do not correlate to true uplift. Increasingly, marketers apply more sophisticated attribution approaches that seek to identify touchpoints contributing to true uplift, disregarding those that simply managed to drop a cookie on a consumer who was going to convert regardless.

Incorporating data on viewability, removing fraudulent impressions and assigning credit across a full path to conversion is often unkind to the remnant banner ad.

Getting Greedy

While the rapid growth of programmatic display has delivered many benefits for marketers and publishers, some publishers have sought to maximize their available inventory by simply creating more ad slots on every page. While this brought short-term revenue, this influx of inventory was largely low-quality. A banner ad that appears alongside eight others is less likely to be noticed and, of course, those that are stuffed well below the fold have not helped viewability rates, which are generally the lowest for RTB media.

Recognizing a problem with ad stuffing, Google started to penalize web sites with too many ads above the fold in 2012. This is helpful, but does not eliminate all below-the-fold ad stuffing. Furthermore, as publishers add native, video and content ad units, banners have more competition for user attention and engagement.

What Comes Next?

The banner ad has a lot going against it as it approaches 20 years old. Will the banner persevere, evolve and live on for another 20 years? More importantly, should it? Or would the industry be better off if we mutually agreed to kill off the banner and focus on other ad units?

One thing is certain: Publishers will follow the money. As long as bid requests come in for 300×250 pixel standard ad banners, suppliers will have inventory for sale.

While the banner will undoubtedly survive its 20th birthday, I believe we have already passed the peak of the banner era. The next five years will bring the strongest growth in video and in-stream ad formats. While increased activity in programmatic may fuel pockets of display growth in the short-term, expect total impressions for display banners to fall in the coming years as more join the ranks of BuzzFeed, Facebook and Twitter in offering banner-free advertising.

On the banner ad’s 25th birthday, we may well look back and wish the standard banner had been put out of it misery after 20 years.

Follow Marcus Pratt (@mawkus), Mediasmith (@MediasmithInc) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.