“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by David Danziger, vice president of enterprise partnerships at The Trade Desk.

In Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” Juliet famously asked, “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

In 2016, the same might be said of audience data. Companies sell tens of thousands of segments to advertisers to assist them with their targeting.

And just like that, consumers become known as auto intenders, sports enthusiasts, females age 35 to 44, urban sophisticates, homeowners or the 10% most likely to use credit cards for travel.

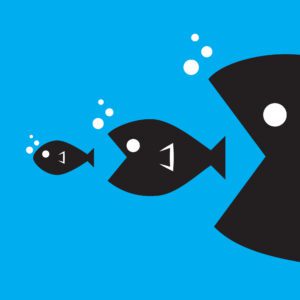

But how much do the users within a segment really fit into these broad stroke categories? Even a cursory glance at some segments can raise eyebrows.

For instance, a segment may show more than 30 million owners of an auto brand whose highest annual sales figure in the last 15 years barely topped 200,000. Or the high-confidence female segments that actually validate at only 55% female.

This isn’t an indictment of data as a whole, but it does mean that segment names are just that: names. The users within the segment may indeed, by the standards of the name, smell as sweet as a rose, or they may instead stink like a pile of garbage.

To understand why this matters, consider how marketers select third-party segments for a particular campaign. The most common method involves entering a search term in a search bar, such as “coffee” or “Starbucks.” They may then use some or all of the segments that show up based on what’s needed for the scale of the campaign.

The name may indeed be a decent starting point, but what’s more important is what’s actually in the segment. Do the individuals within a given third-party segment overindex with a company’s first-party data? If so, then it doesn’t matter whether the segment is called “coffee drinkers” or “truck drivers.” It’s the metrics for the underlying users in the segment that matter.

For example, a retailer that already has a first-party audience consisting of its most valuable customers should be able to understand how closely any general third-party segment aligns with its first-party audience. It may be that an off-the-shelf audience of “Chevy pickup truck owners” overindexes against the retailer’s first-party data more than an off-the-shelf audience of “frequent shopper at retailer competitor A.”

This is why the segment name should not be the decisive factor. The marketer of the future is beginning to connect and attribute value to these segments in addition to the rest of the marketing mix and the customers’ histories and experiences themselves. Marketers have the data in front of them – they just need to know how to use it.

Follow The Trade Desk (@TheTradeDeskInc) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.