“The Sell-Sider” is a column written by the sell-side of the digital media community.

“The Sell-Sider” is a column written by the sell-side of the digital media community.

Today’s column is written by Esco Strong, Director, Display Marketplace Strategy at Microsoft Advertising. Opinions expressed are his own and do not necessarily represent those of his employer.

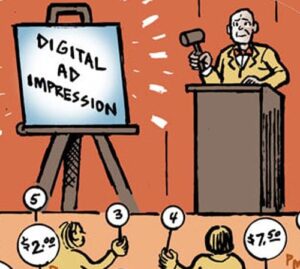

Amidst some of the more popular discussion topics of today, I’m often surprised by the lack of discussion around one of the primary factors underlying key issues such as bidding algorithms, floor pricing, and price discovery: the fact that most RTB auctions are executed as second-price auctions. While this detail is of great importance in defining some of the key dynamics and dominant strategies within those auctions, it is a topic that seems to have flown under the radar of much of the public discourse within our industry. The reality is that many of us simply accept the second-price auction as a fact of life in online display advertising, often without pondering the questions of why that is the case, how we got here, or whether better alternatives to this type of auction exist.

So how did we get here?

The pervasive mode of thinking within our space essentially attributes the second-price auction in RTB to the effectiveness and legacy of that same auction model in paid search. Dig a little deeper, and you’ll find that the second-price auction has its roots in auction design and game theory, and is heavily influenced by the research of top economists such as Paul Milgrom and Preston McAfee that date back to experiences like the FCC spectrum auctions in the late nineties. Essentially, the second-price auction serves as an effective substitute for the single ascending, multi-round (SAMR) auction, which in a nutshell, works as follows:

- Bidders place sealed bids against one another, with the highest bid identified following each round

- Competitors may place subsequent rounds of bidding at some minimum increment above the previous round’s highest bid

- These rounds continue until all but two competitors have exhausted their ability or willingness to pay for the item at current auction pricing

- The bidder with the second-highest willingness to pay submits their maximum possible bid, which is then bested by the bidder with the highest willingness to pay, at a bid price of the value of the second-highest bid plus the minimum bid increment

The second-price auction is really just a quick and dirty way of ‘cutting to the chase’ of this type of auction. It does so by eliminating the song and dance of the earlier rounds of sealed bidding by simply requiring each bidder to initially submit their maximum willingness to pay – also referred to as ‘true private value’ (TPV). The auction will then calculate the same outcome and price as a SAMR auction, where the winner pays the second-highest bid plus a minimum increment. This seems like a reasonable tradeoff that allows these auctions to happen in near real-time, satisfying the requirements of delivering an ad decision to a user’s browser or app fast enough to not interfere with their experience, while replicating the desired outcomes of performing a SAMR auction in determining a fair price for both buyer and seller.

The Fallacy of the True Private Value Bid

But this reasonable facsimile is only a valid alternative to the SAMR auction if some basic assumptions hold; primary amongst these assumptions being the willingness of the bidders to submit their true maximum private values for the item being auctioned. To make matters worse, this assumption itself largely relies on the additional assumption that the auction is for a truly unique item, and not one for which there is a readily available substitute.

The reality is that the required condition of TPV bidding clearly does not hold true for RTB auctions due to a variety of issues. First, the items being auctioned off are not unique, as these auctions are replayed over and over against the same inventory units, users, ad sizes, etc. Buyers are also dealing with finite budgets, and are often trying to achieve particular volume or rate targets within those constraints. As such, there are elements of both substitutability and repetition involved that create a situation where bidding one’s true private value is not the dominant strategy. Instead, bidders learn over time the values they will need to pay relative to the market to acquire the good, and game theory suggests they will instead vary or test their bid values to try to acquire the sum total of goods they need at the lowest rates possible through substitution.

Sometimes this concern is explained away with the argument that, given sufficient bid density within a mature marketplace, the second-price model effectively collapses back to a first-price auction. But due to the way that RTB’s technology infrastructure has developed, demand is often aggregated through demand-side platforms which typically host pre-auctions or optimize across their bidders, consolidating many different potential bidders into one single bid that is submitted to the marketplace. This reduces bid density and breaks the second-price auction, which assumes all possible bidders are participating and submitting their TPV. It is also of note that this issue pertains to display RTB auctions but does not affect search due to the multiple-winner format of those auctions. Therefore it is possible to rationalize the second-price auction model in search as one that effectively behaves like first-price due to bid density, but the same does not apply to the display RTB auctions of today.

AdExchanger Daily

Get our editors’ roundup delivered to your inbox every weekday.

Daily Roundup

The Fallout

This poses a curious position for buyers and sellers alike within these auctions. Buyers face a landscape where they know the best option for them is not to behave in the manner prescribed by second-price auction theory, particularly when they will be competing with others facing a similar choice. Sellers, on the other hand, are willingly reducing clearing prices on their inventory based on the assumption that all buyers are bidding their true values, an assumption which informed sellers cannot realistically believe to be true. Add these two sides of the equation together, and the result is a marketplace where there are broken mechanics based off of faulty assumptions, the specter of suspicion and distrust (and the corresponding friction that results from them), and gamesmanship in pricing that is causing undue negotiation in what is supposed to be a very efficient, streamlined market.

One great example of this is the recent stir in response to various marketplaces and sellers moving towards dynamically generated pricing floors. Common perceptions are that these are little more than methods by which sellers will fool buyers into believing their bids will be price reduced through the second-pricing mechanism, only to have the rug pulled from beneath them by algorithms that mimic their bid and effectively make them pay their first price. There may be some sellers that are, in fact, employing this method, which I find quite difficult to understand. Wouldn’t it be simpler to just convert those auctions into first-price auctions and be transparent with buyers? Not only would this option eliminate the ill feelings on both sides, but it would also save both parties from investing in technologies that are aimed squarely at one-upping one another in what should otherwise be an amicable transaction between business partners. On the other side of this aisle, I believe that there are some buyers today that bid their true private values and rely on price reductions to find their margins. But this is hardly the pervasive behavior and, as such, the irony is not lost that in the hullabaloo over floor pricing, bidders not expressing their true values is being overlooked entirely as a key contributor to the problem.

The Solution

We are at a decision point in our industry where there are two clear possibilities ahead of us. We can choose the status quo of fantasy life, where we pretend that our auctions are well-suited to a second-price model and subsequently live with the difficulties that come with that, including escalating pricing arms races and transactional friction between buyers and sellers. Or we can choose a different path – one where we recognize the inconsistencies and faulty assumptions of our current model, and correct the auction mechanics as best possible in the interest of efficiency and growth. I believe we should pursue the latter option by switching to first-price auctions, where competitive optimization by individual bidders can be acknowledged and accepted, and sellers will not have to innovate around a broken system that only works against their best interests. Comparatively, first-price auctions are competitions where there is no reduction in clearing price for the auction winner; instead, the winner simply acquires the good they have won by paying the price of their bid. The dynamics of this type of marketplace would become much more straightforward and predictable, enabling more parties to participate and experience stable results, as well as manage their businesses to a of set expectations that won’t require constant revision. What you see is what you get, to put it bluntly.

Would this reduce our RTB marketplaces to some sort of Pleasantville-esque utopia of straightforwardness, or, on the other end of the spectrum, some degeneratively over-simplified market where the next great technology innovation will be stifled and unable to succeed? I hardly believe either of those scenarios to be possible – we will still have plenty of complexity to deal with, and other challenges will live on for someone with the right set of smarts and technology to make a lot of money solving against them. But it would be a welcome change to see this particular game of cat-and-mouse eliminated so that we can all move on as quickly as possible to solving those more important challenges. What do you think?

Follow Microsoft Advertising (@msadvertising) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.