“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Tom Triscari, CEO of Labmatik. It is a response to “Advertisers May Unknowingly Add To The Industry’s Fraud Problem,” posted on AdExchanger on April 23.

The interplay of demand, supply and fraud incentives is a fascinating area of study. A recent AdExchanger post by Hagai Shechter, CEO and founder at Fraudlogix, is consistent with current imbalances typically found as markets move from cobbled states to more mature states.

Hagai argues that poorly aligned advertiser KPIs can promote the persistent need for impression and/or click fraud, highlighting one of many nuanced drivers that needs to be brought to the surface. Below I present his argument as a math case and show how it might pan out in the real world.

The math case premise is based on what Hagai described as “perverse incentives”:

“This collective trend toward improving traffic quality – but only up to a point – occurs in part because advertisers’ success metrics are skewed to a fraud-ridden market. The advertisers are used to working with and around the fraud. They expect it, and their target metrics are calibrated accordingly.”

Despite all the obvious upside programmatic has already created, there is much more upside to be gained when incentive alignment improves. Today, too much brand budget is left on the table when simple changes can make it go much further.

The perverse math case

Imagine an advertiser running a $10,000 upper-funnel branding campaign. The advertiser’s primary KPI is to get 10,000 clicks.

The advertiser relies on an agency, trading desk or managed service DSP to hit this simply defined KPI. What this case highlights is how simple KPIs can result in the unintended consequence of completely missing the objective, not even knowing it and repeating the same exercise again and again.

Here is our case question:

Given the following campaign information in the table below, how much budget was wasted on bad impressions and what is the advertiser’s eCPC and eCPM?

Had the advertiser given his managed service provider opposing min-max constraints such as “maximize the number of real human clicks and also minimize impressions wasted by non-viewable inventory,” what would be the optimal eCPC and maximum number of real human clicks?

Table A: Managed DSP runs this campaign…

| CPM | % Imp | Assumed CTR | |

| Publisher Segment A | $10.00 | 25% | 0.50% |

| Publisher Segment B | $5.00 | 25% | 0.25% |

| Publisher Segment C | $1.00 | 25% | 0.10% |

| Publisher Segment D | $0.50 | 25% | 0.10% |

Table B: The campaign truth of what really happened…

| Fraud / Non-viewable | Fake clicks | |

| Publisher Segment A | 0% | 0% |

| Publisher Segment B | 10% | 5% |

| Publisher Segment C | 40% | 30% |

| Publisher Segment D | 80% | 50% |

Breaking down the case

The end-of-campaign report will show 10,000 clicks on 8.25 million impressions. The unadjusted eCPM is $1.21 ($10k / 8.25 million impressions) and the eCPC is $1.00. Well done. Both sides of the trade walk away feeling accomplished. This is exactly what the advertiser asked his managed DSP service to deliver by mutually determining goal achievement. Not so fast.

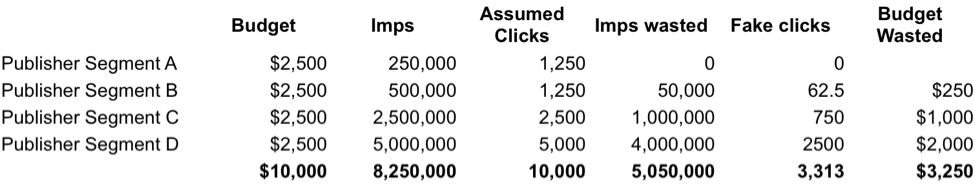

After we factor in the campaign truth we get an eCPM of $3.13 and an eCPC of $1.50. This result is way more expensive than what was reported. (Tables C and D below show the adjusted campaign results.)

Table C: Results

After adjusting for non-viewable impressions along with click fraud (separate yet related buckets), we find 3.2 million bad impressions. The real CPM increases and so does the real CPC.

Table D: Summary

| Good impressions | 3,200,000 |

| eCPM | $3.13 |

| Real clicks | 6,688 |

| eCPC | $1.50 |

| Cost of bad impressions | $3,250 |

The root of the KPI problem

The advertiser thinks he is going for a specific goal of 10,000 clicks. But what he really is trying to do is “maximize the number of real human clicks and minimize impressions wasted by non-viewable inventory.” This min-max approach is a very different perspective that changes the entire media plan toward value creation as opposed to negotiated value creation.

Had this been the objective, the advertiser converts the wasted $3,250 from non-viewable inventory into impressions that get clicks. If this “found” budget was split 50/50 between publishers A and B, both with higher CPMs and better inventory, the advertiser would have gained 1,584 more clicks (incremental clicks less minimized 5% fraud waste) totaling 8,272 and paid a real eCPC of $1.20.

Using min-max strategies works. And it all starts with asking two questions to avoid unintended consequences: What are you really trying to achieve? And how do you determine you achieved it?

Follow Tom Triscari (@triscari) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.