“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Alan Chapell, president at Chapell & Associates.

I recently provided commentary for a Wall Street Journal article about the Do Not Track (DNT) proposal being crafted by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), a well-known standards group. DNT was conceived as a privacy protective tool more than three years ago, and was popularized by the former chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, who is now a telecom lobbyist.

Conceptually, DNT sounds tantalizingly simple. The basic idea is to place a button on browsers that empowers consumers to tell websites not to track them. And when consumers click on that button, tracking would stop. It certainly sounds simple, but once you dig into the weeds of what DNT actually does, things get complex very quickly. What becomes very clear is that DNT helps a few big companies without doing much for privacy.

Proponents of DNT claim DNT will stop online data collection but this is categorically not true. DNT is specifically designed to stop the collection of data by independent third-party advertising technology companies. It won’t, however, stop data collection from Google+ buttons or Facebook widgets. It also won’t stop The New York Times from working with data brokers to target ads on its site. And it won’t stop Amazon from creating its own advertising network across the Web.

In other words, Do Not Track does not stop tracking.

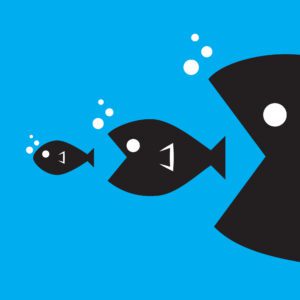

Instead it allows some companies to track but prohibits other types from tracking. By design, the types of companies that can’t track are small and the types of companies that can are large.

Why would a working group like W3C, which is dedicated to a privacy concept, be OK with such an outcome?

Here’s one possibility. The W3C tracking protection working group receives additional funding from a handful of large companies. It is difficult to know if all funders have been disclosed, as the W3C remarkably does not have a policy requiring disclosure of its funders. I think it’s clear that large companies are bankrolling the W3C tracking protection initiative and driving the agenda of the tracking protection working group. The working group’s editors and co-chairs include Google, Apple, Intel and Adobe. I’m not the first person to allege that the W3C is dominated by large companies.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the large companies that dominate the working group have all been successfully exempted from DNT’s primary requirements. Essentially, a group of large companies have banded together to create a privacy standard that applies to one segment of the market – small ad tech firms – while largely exempting another segment of the market – big firms like Facebook, Apple and Microsoft. Regulators and privacy advocates have mostly chosen to remain silent on the anticompetitive concerns despite several calls to action. Some privacy advocates have even admitted that focusing solely on third-party advertising technology companies was part of a compromise with the large companies.

Other privacy advocates, like group co-chair Justin Brookman of the Center for Democracy and Technology, justify this outcome because consumers have a direct relationship with Facebook and Google but not with third-party advertising networks. In other words, Facebook and Google are established brands with a strong incentive to do right by their customers. Regulators have made similar arguments.

This logic is built on a few faulty premises:

1. Consumers really ‘know’ big Internet companies

Branding is very context-specific. While I might “know” Amazon because it offers a fantastic retail and ecommerce platform, my relationship is with Amazon the retailer. Price, reliability and site functionality come to mind. But I do not know Amazon as an advertising network. My relationship with Amazon doesn’t extend that far. If we genuinely believe it is a societal good to reign in ad networks’ use of data, we should apply those regulations to all ad networks.

2. B2B brands are not subject to market pressure

This argument assumes that advertising networks and other companies operating in a B2B marketplace are not subject to market pressures. Under this logic, B2B companies don’t need to worry about adhering to strict privacy standards. That notion is categorically false. There is a long history of B2B companies that have been sanctioned and even put out of business for failing to do the right thing.

3. B2C market pressure can sufficiently reign in large firms’ privacy practices

More than one Internet giant is under an FTC consent order for privacy violations, yet they continue to push the envelope on privacy. The current trend for Internet giants is to consolidate all data collection into a single privacy policy. And while that practice has raised issues with regulators, it doesn’t seem to have any discernable impact on consumer behavior.

So, despite the rosy promises, Do Not Track actually creates a perverse set of outcomes, favoring big companies over small with little privacy benefit, and where the only solution for small companies would be to get acquired by big consumer-facing companies. While I’m sure that this is good for Google and Facebook, it is not so great for either privacy or innovation.

Follow Alan Chapell (@chapell68) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.