As the ad industry girds for the mushrooming debate around privacy, consumer choice and ad blocking, it’s clear that existing opt-out mechanisms aren’t exactly cutting it, especially when it comes to cross-device.

As the ad industry girds for the mushrooming debate around privacy, consumer choice and ad blocking, it’s clear that existing opt-out mechanisms aren’t exactly cutting it, especially when it comes to cross-device.

But although mobile adds another layer of complexity to the situation, online advertising is still reliant on a little .txt file called the cookie, the frail backbone of online opt-outs, which Stanford privacy researcher Jonathan Mayer called a “boneheaded means of implementing consumer choice.”

First Off: Cookies

“Cookies are very fragile,” Mayer said, “They’re not exactly what you want in place when consumers are trying to exercise firm privacy choices.”

Part of that has to do with consumer expectation. When users opt out of tracking, they expect their wishes to be remembered. But when cookies are cleared, user preferences usually get cleared right along with them – a less-than-ideal situation for protecting privacy.

Although the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA), a consortium comprised of advertising and marketing trade groups, created a browser extension called Protect My Choices that professes to help users prevent the accidental deletion of their opt-out cookies, it’s far from foolproof.

As Mayer recently pointed out on his blog, Protect My Choices is built from the same code base as the now deprecated Keep My Opt-Outs extension from Google, which has since been folded into the DAA’s efforts.

Protect My Choices works by creating an internal list of advertising companies and associated opt-out cookies. If/when a user unintentionally deletes an opt-out cookie, the extension simply reverses the action. But the extension’s functionality is only as effective as that aforementioned internal list of cookies, which needs to be continually updated to include new companies, an action that happens upon the release of a new version, not automatically.

[In Mayer’s post, dated June 1, he noted that the Protect My Choices extension had not been updated since July 2014. A quick trip to the Chrome Web Store shows that a new version of Protect My Choices was released on June 6.]

The unreliable nature of cookies makes some advertisers apprehensive when it comes to taking advantage of cross-device linkages.

Adobe experienced some of that pushback firsthand when it presented the concept for its forthcoming cross-device data co-op to a group of 30 brand clients and partners on a June 24 conference call, a recording of which was obtained by AdExchanger.

After Vinay Goel, Adobe’s privacy product manager, explained Adobe’s classic cookie-based system requiring users to opt out on a per-device basis each time they clear their cookies, one of the clients on the call called foul. [Adobe, however, also proposed a novel mechanism that would allow users to see which of their specific devices have been linked together.]

“It feels like an infinity loop,” the client said, referring to the need for consumers to be constantly maintaining their preferences in a cookie-based system. “I like the idea of the co-op … but it feels like the opt-out option is kind of flawed.”

And it is. Goel readily acknowledged as much, but with a slight deflection. “This is an industry challenge, not just an Adobe challenge,” he said.

But the industry doesn’t have much in the way of other options at the moment.

“The way almost every Internet marketing technology works today, if you clear your cookies and then the consumer comes back to the site, they are being targeted and profiled again,” Goel told Adobe clients on the call. “This is one of the limitations or challenges with cookie-based opt-outs.”

Easy Way Out?

There is an inherent conundrum at the heart of cookie-based opt-out mechanisms.

Some websites ironically continue tracking a user that has opted out in order to “remember” not to show that person targeted advertising, storing the opt-out preferences on the server side.

Other companies, including Google, stop tracking users and store nothing other than the opt-out preference at the browser level. In that scenario, the opt-out preference is saved by setting the ID cookie to something like “OPT_OUT.”

The AdChoices icon, that diminutive blue symbol that has appeared since 2012 in the corner of banner ads courtesy of the DAA – Mayer sardonically noted it “looks like a play button” – claims to give users control over the way browsing data is collected and used in interest-based advertising, although the opt-out in that case only applies to companies participating in the program. There’s no guarantee that a user won’t – and indeed, it’s likely that a user will – still see behaviorally targeted advertising online.

The AdChoices icon, that diminutive blue symbol that has appeared since 2012 in the corner of banner ads courtesy of the DAA – Mayer sardonically noted it “looks like a play button” – claims to give users control over the way browsing data is collected and used in interest-based advertising, although the opt-out in that case only applies to companies participating in the program. There’s no guarantee that a user won’t – and indeed, it’s likely that a user will – still see behaviorally targeted advertising online.

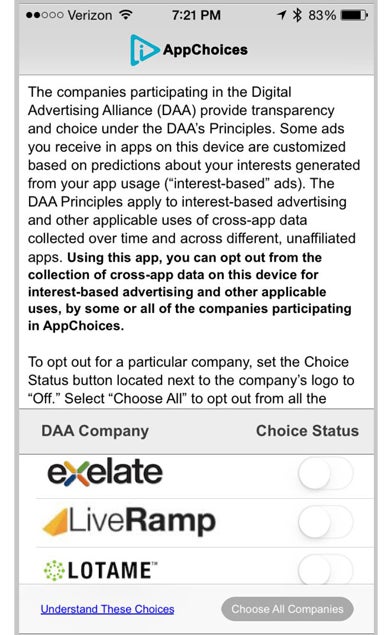

But all of that is just desktop-related. In February, the DAA extended its AdChoices program to mobile with the launch of AppChoices, which ties the opt-out to a device ID, as well as the release of a consumer choice page for the mobile web to help consumers manage their mobile preferences based on their cross-app behavior. Independent enforcement of the DAA’s mobile guidelines begins Sept. 1 by the Council of Better Business Bureaus and the Direct Marketing Association.

The alternative to mobile cookies is an advertising identifier, like the ones provided by Apple, Google and Microsoft. These allow consumers to opt out of targeted advertising by either limiting tracking or resetting their ad ID, the equivalent of cookie clearing.

“These mobile platforms also provide end users visibility into how they are being tracked by providing notifications and access options by app on a single screen,” said Saira Nayak, chief privacy officer at mobile attribution company TUNE. “This allows consumers to better manage the many data relationships they have with mobile apps and websites.”

However, there’s no such thing as a truly universal opt-out, at least not today. If users don’t want to be tracked, they have to diligently set and maintain their preferences per individual browser and per individual device.

Not to mention that the saga around Do Not Track lumbers on. After a decade of back and forth, all major browsers, including Firefox and Chrome, finally support DNT, but there’s no real enforcement behind it. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, Disconnect, Adblock, DuckDuckGo and several others announced in early August that they are working together to publish a stronger standard with teeth.

… And Now Comes Cross-Device

Cross-device linkages come in two basic flavors: deterministic and probabilistic. Companies like Facebook or Twitter can use logged-in users to sync and link, which also applies to cross-device privacy preferences. Companies like Drawbridge and Tapad rely on creating probable linkages based on observations made over time.

“When folks in the advertising space talk about scaling up cross-device tracking in an exchange, they tend to be talking about a probabilistic solution and that introduces some challenges,” Mayer said. “If they offer an opt-out, they can only do so with a likelihood, but no guarantee, that the opt-out will transfer to other devices.”

It’s a “weird choice to offer,” he said, which is why users are asked to opt out on each one of their devices to make sure.

Although Drawbridge, for example, offers what it calls “universal cross-device opt-out,” which allows users to nullify the linkages between their devices within Drawbridge’s connected consumer graph with one click, the opt-out policy on Drawbridge’s website carries more tempered language: “Because we can’t tell you’re opted out on different devices (for example, your laptop and your mobile phone), you should complete the opt-out process for all devices and browsers you use.”

Do Consumers Get It?

“It’s the Wild West in terms of managing this and coming at it from the user perspective,” said Brienna Pinnow, product lead for addressable advertising at Experian Marketing Services. “How can the consumer understand this ecosystem if we ourselves are struggling with the best way to do it?”

Take the AdChoices icon. A study conducted in March by ORC International for Kelly Scott Madison found that 74% of consumers were not aware of the ad campaign the DAA launched in 2012 to spread awareness of the little blue button. The study also noted that even when consumers had heard of the program, nearly two-thirds didn’t know what it meant.

[Anecdotally, I recently showed my 70-year-old father a banner ad with the AdChoices icon in the corner and asked him where he thought he’d have to click to opt out of seeing targeted advertising. He a) didn’t notice the AdChoices icon; b) had never seen it before; and c) was irked when I explained its purpose. “You can’t even see it,” he said, peering at the screen.]

Mayer is skeptical as well.

“Those little icons are just another example of how to look like you’re giving folks a choice while at the same time ensuring that they don’t exercise that choice,” Mayer said. “It’s yet another instance of design for the purpose of the appearance of a privacy choice without actually facilitating that privacy choice. I call it privacy theater. You do all the window dressings to make it look OK, but you’re not doing it seriously.”

According to the DAA, more than 6 million people have registered their web preferences since the AdChoices program launched. AppChoices, which launched in February, has been downloaded “thousands” of times since then, although the DAA declined to elaborate.

AppChoices – which admittedly relies on a device ID-based opt-out and not on a cookie-based one – seems to suffer from the same disease as many existing opt-out mechanisms: It’s a lot of work for the user.

Users who take the time to find it in an app store are presented upon opening the app with a large block of uninviting text above a scrollable list of participating ad tech vendors they’ve more than likely never heard of. Users are invited to learn more about each company by tapping on its logo, which brings up a large paragraph of marketing boilerplate.

Users who take the time to find it in an app store are presented upon opening the app with a large block of uninviting text above a scrollable list of participating ad tech vendors they’ve more than likely never heard of. Users are invited to learn more about each company by tapping on its logo, which brings up a large paragraph of marketing boilerplate.

For example, users have to plow through phrases such as, “Through our analytics, smart data and cloud infrastructure products, we power smarter marketing decisions worldwide,” or “The company’s unique data and technology assets enable its clients to connect with their target audience as they move across screens, media and moments.”

Users can either opt out of companies one by one or “choose all companies” and opt out of everything at once. There are 23 companies on the list, including Drawbridge, MediaMath, Millennial Media, Rocket Fuel, Tapad, xAd and Xaxis – but it’s difficult to imagine the average consumer taking the time to wade through all of that promotional mumbo jumbo.

The DAA, of course, sees it differently.

“Right now, the granularity of the opt-out can be as simple as two clicks – you click on the cookie-based choice tool and you download AppChoices and you’re done, you’ve covered your bases,” said DAA executive director Lou Mastria. “It’s not terribly granular. Consumers don’t really want to spend a lot of time understanding the technology, but they do want the choice.”

According to Mastria, the DAA is in the process of conducting internal research with a group of brands, publishers, ad networks, agencies and direct marketers to develop further specific guidance around opting out of cross-device tracking. Details were not forthcoming.

Opt Out In

Of course, the real goal is to give users some kind of understandable value exchange so that they don’t want to opt out at all. Talking about opt-out without talking about the quality of online content, targeting and advertising is like talking about a bad restaurant that offers every customer a full refund rather than improving its food.

“Opting out is hard and it’s hard on purpose,” said Mike Schneider, VP of marketing at location data company Skyhook Wireless. “But I want to make it so that people don’t have or want to opt out, so they understand what they’re going to get if they opt in.”

According to a March 2014 report from privacy management company TRUSTe, 39% of US consumers are actually willing to share their personal data with advertisers in return for more personalized ad experiences.

To TUNE’s Nayak that signals an opportunity for the ad industry to do a better job of explaining the potential value exchange of behavioral advertising.

“Rather than finding the most comprehensive or technologically persistent way to opt users out, the real question is, how can we maintain trust and keep users engaged and opted in?” Nayak said.

If that doesn’t happen, consumers are more likely to get annoyed and flip the ad-blocking switch, which, Mayer said, is far from the ideal outcome.

“Opt-out cookies remain a distraction – we know they’re difficult to use and a poor technical design,” said Mayer. “The best privacy option, for now, is to block advertisements, which is unfortunate.”