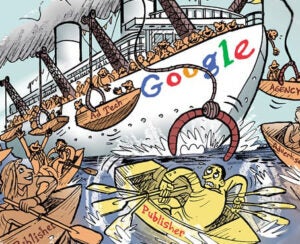

Someone will eventually need to make a Netflix-style documentary about the Google ad tech antitrust trial happening in Virginia. (And can we call it “You’ve Been Ad Served”?)

Because certain moments from Friday alone – Day Five – are just too good to only live on in a court transcript.

The real world

Take, for example, the back-and-forth about Prebid’s functionality that took place between one of Google’s lawyers and Tom Kershaw, Magnite’s former CTO and a co-founder of Prebid.org.

The day before, while cross-examining Jed Dederick, CRO of The Trade Desk, Google’s defense team had floated the notion that one reason Google doesn’t have a monopoly over the ad server market is because it’s possible to use Prebid without also needing an ad server.

It was a strange contention that the DOJ didn’t address during its examination of Dederick.

And so, on the following day, with Kershaw on the stand, Google’s attorney set what he clearly believed to be a trap. He asked Kershaw whether publishers could circumvent the ad server using a Prebid wrapper.

“There’s no way for Prebid to place ads on the page,” Kershaw said.

The lawyer pounced and pulled up a screengrab from the Prebid website with instructions for how to run Prebid.js without an ad server, including what javascript code to use. Kershaw wasn’t rattled in the slightest and calmly reiterated his statement.

At which point Judge Leonie Brinkema, who’s presiding over the case, turned to Kershaw and asked whether it was, indeed, technically possible or not.

To which Kershaw answered: “It’s like saying I could walk to China right now – which I could, but it would be very difficult.” From a practical perspective, he said, no scaled publisher can function without an ad server.

Google’s attorney seized on the words “no scaled publisher.” Aha, he said, so could small and medium-size businesses use this javascript to run auctions and render ads without an ad server?

Kershaw was unflappable. “SMBs can barely fire up a laptop,” he said, “let alone put javascript on a page.”

He went on to explain that Prebid.org is like a scientific organization. It’s made up of engineers that run experiments, mostly to play and learn. Not everything they do is meant to have a practical application. (In fact, right there on the screengrab that Google’s defense entered into evidence, it says, “This example uses a test version of Prebid.js hosted on our CDN that is not recommended for production use.”)

Prebid isn’t magic; it’s just an open-source framework that facilitates header bidding. It’s a line item in DFP. And if publishers want Google ad demand, they still need to use AdX. Kershaw said he’s not aware of any publisher that ever turned off AdX.

Oh, Google’s lawyer said, so has Kershaw done a personal survey of all publishers then?

Obviously not, Kershaw said, and that’s not the point. There’s what’s theoretically possible and then there’s reality.

Kershaw said that he was only there to explain how things work in the real world.

And if you want the real world – or, at least, Google’s unvarnished perspective – it doesn’t get realer than internal emails and confidential slide decks.

After Kershaw, Chris LaSala, Google’s former global product and strategy lead for sell-side ad products, took the stand. And the DOJ used it as an opportunity to enter a stack of emails into evidence.

A big part of LaSala’s job involved commercial strategy, which meant he had some input on AdX fees and Google’s approach to discounts.

Google has long charged a 20% take rate for AdX, which hasn’t budged in years. And according to an internal document from 2017, a mere 13 large publishers out of 3,815 running open auctions (OA) were being given a discounted rate at an average rev share of 19.8%.

LaSala acknowledged during his direct examination that discounts were “rare.” The DOJ then demonstrated that discounts weren’t only rare but deeply discouraged.

The document includes a reference to Google’s annual review of fees for its programmatic display products and says that “for OA there is no evidence that we need to change the rate card due to the limited amount of exceptions and limited amount of discounted revenue.”

And then there’s this line (with the bolded words retained from the original): “OA discounts are last resort, we are holding firm on this position.”

In other words, Google could take its rather large cut of nearly every transaction secure in the knowledge that most publishers were too locked in and dependent on AdX demand to churn or to negotiate lower rates.

‘Irrationally high rent from AdX’

To drive home its point, the DOJ entered into evidence a flurry of frank communications between LaSala and other Google executives.

![]() LaSala in June 2018: “The AdX sell-side fee of 20% holds today not because there is 20% of value in comparing 2 bids to one another, but because it comes with unique demand via AdWords that is not available any other way.”

LaSala in June 2018: “The AdX sell-side fee of 20% holds today not because there is 20% of value in comparing 2 bids to one another, but because it comes with unique demand via AdWords that is not available any other way.”

![]() Then there’s this comment LaSala left on an undated document about revisiting the AdX fee structure: “We need to up our game and focus on winning this game vs. continuing to extract irrationally high rent from AdX.”

Then there’s this comment LaSala left on an undated document about revisiting the AdX fee structure: “We need to up our game and focus on winning this game vs. continuing to extract irrationally high rent from AdX.”

![]() He goes on: “One might ask why the market continues to bear 20%. It may be because of adwords bringing liquidity from a long-tail.”

He goes on: “One might ask why the market continues to bear 20%. It may be because of adwords bringing liquidity from a long-tail.”

![]() January 2019: “We can only retain 20% rev share given AdX mostly brings unique demand in GDN. … I’m still convinced that is the only reason we can sustain 20%.”

January 2019: “We can only retain 20% rev share given AdX mostly brings unique demand in GDN. … I’m still convinced that is the only reason we can sustain 20%.”

![]() And later on: “My summary POV is that a sell-side rev share should probably top out at 10% for OA.”

And later on: “My summary POV is that a sell-side rev share should probably top out at 10% for OA.”

![]() October 2019: “The ‘middle’ does take an outsized share and we are only part of the middle. Yet, one could argue that when we are the middle for both buy and sell sides, we are taking an outsized share.”

October 2019: “The ‘middle’ does take an outsized share and we are only part of the middle. Yet, one could argue that when we are the middle for both buy and sell sides, we are taking an outsized share.”

In that same October 2019 email, LaSala goes on to argue that publishers only gripe about this outsized share because Google has its fingers in multiple pies: network, ad server, exchange and DSP.

“When a buyer brings incremental demand in a network model – pubs don’t seem to complain. Nobody complains about the take-rate from FB, Criteo, AMZ, Google Ads through AFC or AdMob … they only complain about the take-rate when we are pipes.

To the extent we want to be in the ‘pipes biz’ (DV3 or AdManager) we should accept downward pressure UNLESS we can tie our buy and sellsides together to create unique, differentiated value to buyers and sellers. Whether this is through data, protections, scale, etc is up to use. But expect the market to always put pressure on the pricing of pipes.”

The DOJ highlighted this email for obvious reasons, but LaSala sought to clarify.

“Nuance is getting lost here,” he told the court.

LaSala said that he thought Google should have gotten out of the ad tech business altogether and operated as a closed network. Then it could focus on using its data to compete with Amazon and Facebook as a classic walled garden, which is far less messy than owning an exchange and a demand source.

“I was almost alone in this view,” LaSala said. “I didn’t like this business and I was trying to advocate that.”

If that’s true, maybe someone at Google should have listened to him. Because in that case, there wouldn’t be a case.

And speaking of objections, a little over halfway through LaSala’s direct examination, the DOJ was attempting to enter another email into evidence – one in which he refers to the “existential threat posed by Header Bidding and FAN” – and Judge Brinkema asked if the defense had any objection. LaSala thought they were talking to him and so he called out, “Objection!” Judge Brinkema looked his way and told him, kindly, that he should leave that to the lawyers, to which Chris quipped, “Well, I object to all of this!” The courtroom erupted into laughter, and we all clearly need to get out more.

Say ‘Jedi Blue’ without saying Jedi Blue

Say ‘Jedi Blue’ without saying Jedi Blue

The so-called existential threat posed by header bidding and FAN are topics that this next witness could speak to directly: Brian Boland, Facebook’s former VP of ad tech and publisher solutions.

Boland’s testimony touched on a bunch of issues, including Facebook’s inability to launch a viable DFP competitor or secure a real foothold in display advertising. In 2019, Facebook shut off all web supply within its audience network.

But before that, Facebook was still angling for network scale, and the biggest impediment, Boland wrote in an August 2016 email, is that “Google sits between the publisher and Facebook.”

“We have seen them take very aggressive steps once they have a footprint,” Boland wrote. “I would hate for DCLK [DoubleClick] to use AN [Audience Network] to gain a strong mediation foothold and then bias their system against us – much like they do on desktop, where ‘dynamic allocation’ gives Google the opportunity to cherry pick the best supply.”

But hey, maybe Google just has the superior product, and if that’s the case, does any of this still matter?

It does – a lot, Boland said. When Google was gatekeeping the best inventory for itself through practices like first or last look, that necessarily reduced the overall number of available quality impressions.

Boland shared an analogy: If someone comes and takes the best 30 apples out of a barrel to sell and only leaves bruised and blemished ones behind for everyone else, it’s a foregone conclusion that the cherry picker is going to sell more apples.

Which is why, in early 2017, Facebook saw header bidding as an opportunity for the industry to combat Google’s advantage in the auction.

Yet, by the end of the year, a deal between Facebook and Google was in the works. A December 2017 strategy document about Audience Network includes an action item that says, “Do we move forward with our ad tech partnership strategy and partner with Google?”

This is a reference to what would become the now notorious Jedi Blue arrangement, whereby Facebook agreed to support Google’s open bidding product and not develop one of its own in exchange for lower fees and an advantage ad auctions. Boland confirmed that Facebook and Google negotiated their deal over the course of six or seven months.

(The codename “Jedi Blue” never came up, though. The DOJ referred to it as a “Network Bidding Agreement.”)

And that was pretty much it for Jedi Blue, aka NBA. It got very little attention.

But there was an interesting moment when the government tried to introduce a document (they were overruled) that would have proven Google at one point wanted Facebook to pay 15% of the cost of working media to remove last look, which didn’t happen but sounds like a shakedown.

There were several other witnesses scattered throughout the day.

- Luke Lambert, chief innovation officer at OMD USA, was brought in by the DOJ for yet more questions related to market definition.

He affirmed that “open web display advertising” is a commonly used term in the industry, and then he was asked a bazillion of what felt like meandering questions by the DOJ about attribution, MMM, the marketing funnel, channel planning and optimization. It was a bit like a webinar on marketing basics, but presented under oath.

On cross-examination, the Google defense presented Lambert with a client deck in which OMD groups multiple channels together under the digital display umbrella. This was highlighted as evidence that the “open web display” category is a figment created by the DOJ for the purposes of its case.

“This is just semantics,” Lambert said on redirect, with a little irritation.

- Arnaud Créput, CEO of Equativ, didn’t testify in person. Instead, someone from the DOJ’s office got into the witness box with a copy of Créput’s deposition and read out his side of the “conversation” together with a DOJ attorney reading the part of the questioner. It was like the weirdest play.

Equativ, which used to be called Smart AdServer, unsurprisingly operates an ad server, which is a pretty tough business considering DFP’s position in the market. Créput shared the exact sentiments that one would expect, including that Equativ has had a hell of a time trying to compete with DFP, especially in the US (as if).

It’s hard to compare Equativ, which generated 92 million euros in 2022 – it’s highest-ever year – with Google, whose network business is declining but still makes more than $7 billion a quarter.

According to Créput, Equativ had to also get into the SSP business as a matter of survival. If it hadn’t made that move, “we wouldn’t have a business,” he said.

- And the final witness of the day, also testifying in absentia, was Brian O’Kelley, whose videotaped deposition was played in the courtroom.

As the co-creator of Right Media, the first ad exchange, and as the CEO and founder of AppNexus, O’Kelley knows where a lot of the bodies are buried in his industry because he buried many of them. His testimony – there was only time to screen part of it; the rest will be shown sometime this week – was primarily a walk down ad tech memory lane.

He mentioned that he spent “hundreds of millions of dollars” to try and create a viable alternative to DFP at AppNexus, but never got traction. The product still exists, though, and apparently a few publishers in Europe and Japan still use it.

O’Kelley also called out Google’s data advantage. Making Google Ads demand exclusive to AdX is one thing, but Google also knows a heck of a lot about user behavior. “Diversity of demand is highly valuable in an auction system,” he said.

And that’s a wrap on the first week of the trial, which is way ahead of schedule.

According to DOJ attorney Julia Tarver Wood, the government will most likely finish its case-in-chief this week, and then it’s the defense’s turn to present its case.

Judge Brinkema told counsel on both sides to spend the weekend “narrowing,” as in to make sure that this week’s witnesses don’t get too repetitive with the testimony that’s already been given in week one.

Nearly every day this week, the first witness slot is reserved for a current or former Googler.

Monday starts with Neal Mohan, currently the CEO of YouTube, but whose roots go back to the DoubleClick days. He spent nearly nine years as Google’s SVP of display and video ads.

Tuesday is Nirmal Jayaram, Google’s senior director of engineering

Wednesday will bring Scott Spencer, Google’s former VP of product management for privacy and user truth, who spent more than eight years at DoubleClick before that.

And on Thursday, the DOJ is calling Jonathan Bellack, Google’s former director of product management for publisher ad platforms.

Unfortunately, AdExchanger won’t be in the courtroom this week, but there are other great resources to keep you up to date on the day-to-day, including Arielle Garcia at Check My Ads and Ari Paparo’s Marketecture Monopoly Report. 🤓

And why not check out our past coverage while you’re at it:

- Your Day One Recap: DOJ vs. Google Goes Deep Into The Ad Tech Weeds

- The DOJ vs. Google, Day Two: Tales From The Underbelly Of Ad Tech

- DOJ vs. Google, Your Day Three Download: A Former Googler On The Stand And Auction Dynamics In The Spotlight’

- DOJ vs. Google, Day Four: Behind The Scenes On The Fraught Rollout Of Unified Pricing Rules