Walmart, Nike, Amazon, Dell, Honda, Lowe’s – all brand advertisers you can trust, until a bad actor steals their ad creative to use as a vehicle for spreading malware.

The problem grows during periods of higher traffic, like the holidays, said Maggie Louie, CEO and founder of DEVCON, a cybersecurity startup focused on fraud detection.

Not too many advertisers are aware of this issue, Louie said, and even those that are aware don’t necessarily prioritize it. They’re more focused on not paying for bot traffic.

But it really should be top of mind for all advertisers, said Kate Reinmiller, co-founder and CRO at Ad Lightning, a company that helps publishers find and root out bad ads.

Even if the first incident doesn’t affect an advertiser’s bottom line, turning a blind eye allows more fraud to be seeded into the open ecosystem over time, and that will eventually show up at their doorstop.

It also has the potential to hurt click-through rates across the board – and they’re teeny-tiny to start with.

“There is already just a small percentage of people who click on ads, and that will probably shrink if word gets out that it’s dangerous to even click on a good-looking ad,” said Adam Heimlich, SVP of media at GALE Partners. “It threatens the click-based aspect of display.”

The scheme

Ads are hijacked when fraudsters take real creative assets, usually basic banner ads, and inject them with bad code to run exploits and then deploy the reconfigured ads through programmatic pipes.

If an ad network’s or exchange’s quality assurance process isn’t robust enough – perhaps they’re only looking at the images and text rather than the code within – the fake ad can slip through.

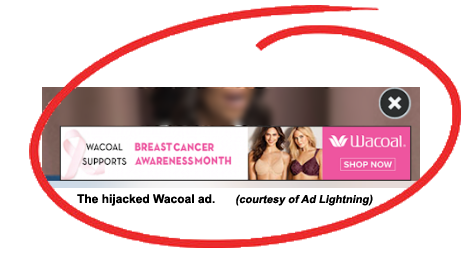

DEVCON came across a Hollister ad in the wild offering users a 50% discount that was really a trojan to distribute malware. Ad Lighting discovered a Wacoal banner during the 2018 holiday season in which the click-through URL was replaced with a malicious domain. Users who tried to “X” out were redirected to the phony site.

“It used to be that malware or mobile redirect code would use generic creative; sometimes it didn’t even look like a real ad,” said Ad Lightning’s CEO and founder, Scott Moore.

“It used to be that malware or mobile redirect code would use generic creative; sometimes it didn’t even look like a real ad,” said Ad Lightning’s CEO and founder, Scott Moore.

“Now, they’re actually stealing Wacoal ads, Wells Fargo ads, Walmart ads, presumably because they’re getting more sophisticated and focused on cloaking what they’re doing, whereas in the past they didn’t really bother with that,” Moore said. “Anybody at an exchange taking a cursory look would see what looks like a real ad and be less likely to dig deeper.”

The victims

As always, the consumer is an easy mark for bad actors looking to spread malware, in this case using real brand logos as a front to establish trust and create a “warm feeling with the end user as fraud is going on in the background,” said Asaf Greiner, CEO and founder of anti-fraud solution provider Protected Media.

But that “warm feeling” can quickly turn cool if a consumer gets infected with malware and associates that experience with a particular brand. Not only is the brand’s IP being stolen, the brand’s reputation is on the line. The user has no idea that the brand isn’t directly responsible.

The question of responsibility is a tricky one, though, because there are so many different points at which the quality control process can break down and malicious code can be injected.

“There are secondary auctions, there’s arbitrage – it’s easy to sneak in,” Reinmiller said.

The supply chain is crowded, said Laura Hudson, VP of Americas at M&C Saatchi Performance.

“It’s unsurprising that the more third-party or middlemen involved in a media buy, the higher the chance of ads being subject to malicious handling,” said Hudson, who noted that clients “would be horrified” to learn that their creative could be used as a springboard to disseminate malware.

A big issue is that SSPs are “allowing any site owner to show up and sell ads, enabling bad actors like the ad thieves or fraudulent sites,” said Oscar Garza, SVP of media activation at GroupM agency Essence. Garza said he hasn’t seen the creative theft problem crop up for his clients yet, but he’s going to double check and stay vigilant now that it’s on the radar.

But demand-side platforms are the most vulnerable as a point of entry, according to Reinmiller, because if fraudsters can get a seat, they can set themselves up as a seemingly genuine entity.

Unfortunately for the supply side, that makes it the de facto last defense for publishers if bad creative is able to ooze its way past the DSP and into the ecosystem.

When supply partners get infected with malware, that immediately hurts publishers because one, a whole segment of their inventory can be driven by bots, and two, they lose out on revenue.

If advertisers start to get hotter under the collar about this, though, DSPs might be even more incentivized to scrutinize their partners, Reinmiller said. Changes happen when feet are held to the fire.

“Malware used to be distributed through creative that no one one cared about, but now that brands are starting to be victimized, there should be more pressure on the DSPs,” she said. “When brands care about something, the DSPs also have to care, and hopefully brands are going to start holding their DSPs accountable.”

The solution?

But is it fair to ask advertisers to monitor for yet even more shenanigans? Google isn’t expected to respond when people send out phishing emails pretending to come from Google, Heimlich said.

But digital marketers do need to be alarmed, he said. Performance display represents a lot of dollars and it’s all centered on getting people to click and buy – yet maybe that’s actually part of the problem.

Click-based strategies don’t work, Heimlich said, whose research into the matter suggests that traffic coming from people who click on ads is not incremental.

“The click-based ecosystem makes sense for search, but display should be closer to a branding mindset,” Heimlich said. “This is just another reason there is a low-quality ad environment.”