Federal law requires ads to be truthful, to not mislead audiences and to be backed up by scientific evidence when necessary.

You can’t just say your product is better than the competition without proof. Or claim to offer “no hidden fees!” when the fine print at the bottom of your ad tells a different story.

The Federal Trade Commission enforces truth in advertising laws with special attention to ads that claim particular benefits to a person’s health or their bank account.

But the FTC only has the resources to bring so many cases to trial. Which is where the National Advertising Division (NAD) comes in.

NAD is a self-regulatory organization that monitors the ad industry for potential false advertising, misleading claims and ineffective disclosures. It handles disputes brought by aggrieved advertisers (like when AT&T objected to a Spectrum Mobile ad that depicted an AT&T store manager actively training an employee to lie to consumers) and it can initiate actions of its own (for instance, when a couple of Kardashians – don’t ask me which ones – failed to disclose in social media posts that they were paid to promote a detox tea product).

Although the NAD’s rulings aren’t binding and it can only make recommendations for a company to correct problematic advertising, the division has the bandwidth to pick up way more cases than the FTC.

The NAD handles around 150 cases annually. And there were some pretty interesting ones over the past year.

Braving the elements

In June, the NAD published its decision from an inquiry into privacy-focused web browser Brave over some of Brave’s privacy-related claims.

At issue were two so-called “express claims,” as in literal statements that Brave made about itself in its advertising (that it “stops online surveillance” and “shields everything … that can destruct your privacy”), as well as one “implied claim.” An implied claim is made indirectly or by inference. In this case, the implied claim was that Brave doesn’t share personal data with third parties.

As part of its inquiry, the NAD examined whether Brave’s privacy protection claims can be substantiated.

To support its claims, Brave pointed to the results of a study it conducted that compared the level of privacy protections for its own anti-tracking tool with the standard privacy settings in Google Chrome. A second study assessed the privacy risks from the exchange of back-end data shared to tech companies as users browse the web.

The NAD found that Brave’s implied claim – that it doesn’t share personal data with third parties – was fair, but recommended that Brave stop making its express claims, because they were unproven by the evidence.

One of the studies, for example, showed that Brave blocked fewer than half of third-party attempts to collect data.

Although the NAD agreed that Brave does offer privacy protection that “might represent best practices in the industry,” it determined that Brave doesn’t fully stop “online surveillance.”

Brave agreed to comply with the NAD’s recommendations.

Remember when the “face with tears of joy” emoji was the Oxford Dictionaries 2015 word of the year?

You could argue that was a PR gimmick, but it also shows how symbols can express ideas, just like spoken or written language.

In November of last year, Stokely-Van Camp, the Pepsi-owned maker of Gatorade, challenged a bunch of express claims in a social media video posted by Bodyarmor, a sports drink manufactured by The Coca-Cola Company.

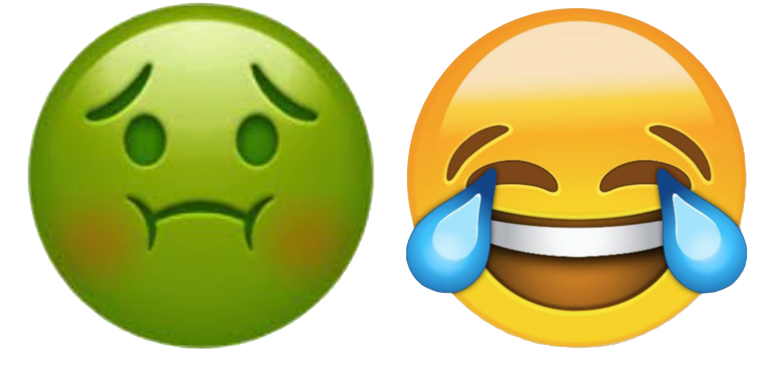

In the post, Cleveland Browns quarterback (and Bodyarmor spokesperson) Baker Mayfield does a supposedly blind taste test of three different Bodyarmor flavors and one Gatorade flavor. He nails the Bodyarmor flavors. But when he’s given Gatorade, he takes a sip while blindfolded and then spits it out while saying, “Yo, that is not cool. That’s awful” as two emoji – the nauseated face emoji and the face with tears of joy emoji – appear superimposed on the screen.

Bodyarmor argued that the post was just a joke with a little “puffery” tossed in and that the meaning of the queasy emoji in question was open to interpretation.

It’s illegal for a company to knowingly lie about a product or service, but puffery is permitted. Puffery is a legal term of art for when companies are promote themselves with hyperbolic or exaggerated claims that can’t be objectively verified because “no reasonable person” would believe them to be factual. (An example of puffery would be something like, “We make the best tacos on Planet Earth!” An example of false advertising would be, “We make the best vegan tacos on Planet Earth!” when in fact the tacos are filled with chicken.)

The NAD didn’t buy Bodyarmor’s defense and determined that Mayfield’s oral statements combined with an emoji on the verge of tossing its cookies (had to get a cookie reference into this article somewhere) attempted and succeeded at conveying a clear and objective message: That Gatorade is gross.

In other words, according to the NAD, an emoji can be used to make brand claims – misleading or otherwise – (so be careful with this one: 💩) and humor isn’t aircover to disparage your competitors.

🫒 … that’s my segue to: “Did you know that 70% of all olive oil is fake?”

Well, it’s not, which is why the false claim above was at the heart of a case brought by the North American Olive Oil Association last year against an olive oil startup called Brightland, which made public claims that “most of the olive oil … sold in the US is rotten, rancid or adulterated” and causes nausea and stomach aches.

Brightland made these claims on its website and on social media. The company’s founder was also quoted in (unsponsored) news articles on third-party websites saying the same. In one case, the phrase “70% of all olive oil is fake,” which was part of a quote within an article, was linked directly back to Brightland’s website.

The NAD recommended that Brightland stop making claims that other olive oil is, well, 💩, including in its advertising, and to remove any links to articles with the challenged claims from its site.

Although Brightland disagreed with the NAD’s take, it agreed to permanently discontinue making its claim about the nastiness of 70% of American olive oil, modify the copy on its site and remove any related links to third-party content.

TL;DR: Back up your claims, don’t be cavalier about your emoji use and don’t malign your competitors with unsupported, misleading claims. 👍