It is “inevitable” that nation-states will try to leverage Facebook and its ad platform to influence elections and political sentiment again as they did during the 2016 presidential election, said Nathaniel Gleicher, Facebook’s director of cybersecurity policy.

It is “inevitable” that nation-states will try to leverage Facebook and its ad platform to influence elections and political sentiment again as they did during the 2016 presidential election, said Nathaniel Gleicher, Facebook’s director of cybersecurity policy.

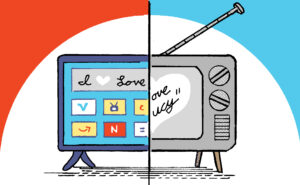

Yet, despite the persistence of false news and misinformation on the platform and likely efforts by bad actors to affect elections, which were cited Tuesday during a sometimes-contentious Q&A with reporters, Facebook’s business is well insulated from even severe controversies or changes to its political advertising.

Dealing with cyberespionage is an expensive, long-term issue, but the company’s revenue growth isn’t at risk.

“Political ads aren’t a large part of our business from a revenue perspective,” said Rob Leathern, Facebook’s ads product manager.

Under Facebook’s new transparency and verification policy implemented in April, only authorized electoral and issues-advocacy advertisers with real-world postal locations can run ads on the platform.

“[We have] definitely seen some folks have indigestion about the process of getting authorized,” Leathern said.

The political policy changes caught some primary candidates off guard in May, resulting in their Facebook advertising being suspended during the critical final days of the campaign.

Facebook is exploring workarounds so candidates won’t get caught in the same authorization bind, Leathern said.

The extent of the policy’s impact on political ad sales this year is unclear.

Where Facebook has effectively clamped down is on the fake accounts and promoted stories that were so effective in 2016 at engaging – and inflaming – people following the election.

Malicious operations, like Russia’s campaign to influence the 2016 US election, relied primarily on fake bots and news content to inflame opinion – and didn’t explicitly support any single candidate.

Pop-up super PACs and accounts created to sow discord will find it much harder to operate – at least without identifiable human beings willing to put their names behind the campaign.

But Facebook said last year that the Russian disinformation campaign in 2016 spent about $100,000 on advertising – a drop in the bucket compared to what legitimate candidates and political groups spend in a presidential election year.