An American associate professor of media design is perhaps not the first person who comes to mind as the driving force behind an effort to test the limits of European data protection law, but there you go.

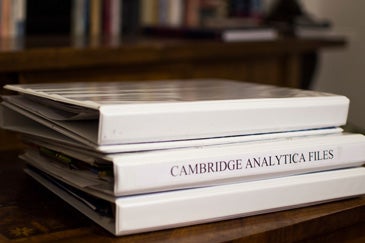

David Carroll, who teaches at the New School’s Parsons School of Design in New York City, is partway through a multiyear legal battle to reclaim his personal data from the now-defunct and bankrupt yet still quite infamous British data analytics company Cambridge Analytica.

But what started out as an exercise of academic curiosity about political profiling has blossomed into an all-consuming project to shine a light on what Carroll calls the “promiscuity” of online data collection and third-party data-sharing relationships.

On Wednesday, Carroll won a minor victory when SCL, Cambridge Analytica’s parent company, pled guilty to breaking British data laws for failing to hand over Carroll’s data. What’s left of Cambridge Analytica – the company filed for bankruptcy in May – was fined £15,000 (roughly $19,000) by the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

But how exactly did a US citizen become such a central figure in Cambridge Analytica’s demise?

Down the rabbit hole

In January 2017, even though he’s not a citizen of the United Kingdom, Carroll filed a subject access request with Cambridge Analytica to get a copy of his data. (This request happened more than a year before the Cambridge Analytica scandal hit the fan for Facebook in March 2018).

A few months later, the company sent Carroll a smattering of 200 or so data points they had on him – his voter registration file, his historical participation in elections, his propensity to vote – but it clearly wasn’t everything they had. When Cambridge Analytica was still kicking, the company used to brag about how it had up to 5,000 data points on more than 200 million US voters. There was also no information on where Cambridge Analytica sourced its data or who else the data may have been shared with.

Carroll filed a complaint with the ICO, the ICO agreed with his thesis that Cambridge Analytica was holding out and the company was ordered to fork over Carroll’s complete data profile, but it still refused on the grounds that Carroll wasn’t a UK citizen, So, the ICO took the company to court. It was a big surprise when the guilty plea came in, though, Carroll told AdExchanger.

“Throughout this whole process, SCL has failed to cooperate, they’ve been evasive, they’ve been misleading and we were all expecting a plea of not guilty – but what’s really crazy about this is that they’d rather be called criminals than just disclose the data,” he said.

Perhaps that’s because Cambridge Analytica data is still being used, likely by ex-staffers starting new business ventures, even though Cambridge Analytica the company is no more.

“We know this because we have GitHub code that shows them connecting to old databases,” Carroll said. “A company is not shut down if former employees can still use assets that are just sitting there in the cloud.”

The fight continues

Separate from his 2017 complaint to the ICO which triggered Wednesday’s guilty plea and fine, Carroll is also suing what remains of Cambridge Analytica for full disclosure of his data. After raising money through a crowdfunding effort, Carroll hired a solicitor and filed his lawsuit in a British court in March … just as former Cambridge Analytica employee Christopher Wylie was blowing the whistle.

Separate from his 2017 complaint to the ICO which triggered Wednesday’s guilty plea and fine, Carroll is also suing what remains of Cambridge Analytica for full disclosure of his data. After raising money through a crowdfunding effort, Carroll hired a solicitor and filed his lawsuit in a British court in March … just as former Cambridge Analytica employee Christopher Wylie was blowing the whistle.

A hearing on March 18 of this year will address the suit and concerns over whether the people in charge of winding down Cambridge Analytica’s operations are doing a proper job or not. Carroll is also hopeful that the hearing could yield the data disclosures he’s been gunning for.

Although it’s possible Carroll will get what he’s after sooner than that. After stalling for the better part of a year, Cambridge Analytica’s administrators finally provided the ICO with the passwords they need to unlock the company servers their agents seized under criminal warrant last year.

Connections

It’s all a bit dramatic. But now, in between semesters at Parsons and the lull between the recent guilty plea and the upcoming trial, Carroll’s had a little time to reflect on his experiences and the road not taken.

Back in 2014, Carroll was trying his hand at being a bit of a tech entrepreneur himself. With backing from Hearst, he and a small team built a machine learning API that could index and analyze images, a bit like Pinterest for magazine archives. Although the initiative didn’t pan out, Carroll recently realized that it weirdly gave him something in common with Aleksandr Kogan and the other academic researchers at Cambridge University who collected Facebook friend data and sold it to Cambridge Analytica.

“In hindsight,” Carroll said, “we were connecting to Facebook, too, and I did have that same moment of, ‘Hey, if you plug into Facebook’s social graph, look at all the data you can get!’ – but then I thought, ‘No, this is completely invasive.’”

But here’s the real takeaway from Carroll’s experience: US-based companies shouldn’t look at the privacy winds a blowin’ as some radical European thing.

When the California Consumer Privacy Act goes into force on Jan. 1, 2020, companies will be compelled to disclose all of the consumer data they collect, including naming third parties the data was shared with. The minimum fine for infractions is $1,000 per person, per violation. A similar clause could also easily make it into a federal privacy law when the time comes.

“Dealing with these requests will be something companies have to get a handle on,” Carroll said. “But, really, it’s also an opportunity for them to decide whether the data they have is an asset or whether it’s actually a liability.”