There’s been plenty of mudslinging in and around the Chrome Privacy Sandbox. But the Protected Audiences API (PAAPI) maybe ain’t so bad.

PAAPI – a proposal for retargeting on Chrome without third-party cookies – could be nearly as effective as retargeting with third-party cookies, according to a new paper by researchers at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business.

Earlier this year, using an unnamed DSP partner, they analyzed retargeting effectiveness across more than 2,000 advertisers for 2% of Chrome users who were randomly assigned to one of three categories:

- Those with third-party cookies turned on to create the baseline (the “status quo” group)

- People who were only retargeted using PAAPI

- A “cookieless” group using neither PAAPI nor cookies

The experiment was devised by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority together with Google to give industry participants an opportunity to test the Sandbox APIs against real traffic.

Unsurprisingly, removing third-party cookies entirely had a hellacious impact on performance. Ad clicks plummeted more than 88%, and ad-attributed conversions dropped by nearly 90% compared with the third-party cookie status quo.

But advertisers using PAAPI for retargeting saw better results – just 47.4% fewer ad clicks and 50.2% fewer ad conversions.

Under the impressions

Hold on, though. 🤨

That sounds pretty bad, actually. Would you skydive out of an airplane if the chance of your parachute opening was only around 50/50?

But those PAAPI performance numbers don’t tell the whole story, said Shunto Kobayashi, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of marketing at BU Questrom.

“You may think, ‘A roughly 50% recovery share? That’s not so good,’” Kobayashi said. “But if you adjust for expenditure, PAAPI works pretty well.”

In other words, PAAPI-powered retargeting appears only half as effective as retargeting using third-party cookies, but that’s because Privacy Sandbox adoption is low across the ad tech ecosystem, particularly among supply-side platforms.

There still isn’t as much ad supply with PAAPI enabled as there are third-party cookie impressions for sale.

When the research results are normalized for ad spend and impression counts, PAAPI is 86.4% as effective as third-party cookies for clicks and 81.8% as effective for click-through conversions per dollar, according to the study.

“We think that PAAPI can work,” Kobayashi said. “The problem is that low industry adoption is hindering its overall effectiveness.”

A bridge to nowhere?

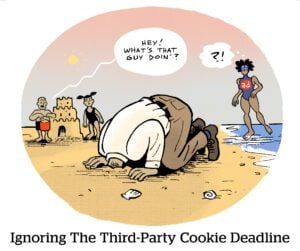

Not that you can really blame the industry for dragging their collective feet (with a few notable exceptions).

The third-party cookie soap opera is about to enter its fifth season, for Pete’s sake, and it’s hard to maintain a sense of urgency about testing a new solution when the only certainty is uncertainty.

And so publishers have started experimenting with other cookieless alternatives, including ID bridging, which involves using first-party data to make matches and recover third-party cookies for bid requests when third-party cookies aren’t available.

There’s been a lot of controversy about ID bridging over the past year.

Publishers are into it, because it helps make their inventory look more valuable in ad auctions. But buyers balked, because many sellers weren’t disclosing the practice. The IAB Tech Lab has since published standards for how to implement ID bridging in a more transparent way.

But here’s a new wrinkle: Kobayashi and his co-authors inadvertently uncovered evidence that ID bridging may not be a viable solution in the long term, at least not for retargeting.

During the experiment, their DSP partner unintentionally bought some cookieless traffic as part of the third-party cookie user group as a result of ID bridging – and they observed a stark decline in the performance of this traffic over time.

The dip is actually quite logical, though, said Garrett Johnson, an associate professor of marketing at BU Questrom and co-author of the report who also serves, fun fact, as an outside expert to the CMA.

As users clear their first-party cookies, the data that publishers rely on to create bridged IDs is deleted, and retargeting is a recency game. The point is to get in front of people who look like they’re about to make a purchase, which means the utility of that behavior signal will degrade quickly.

As users clear their first-party cookies, the data that publishers rely on to create bridged IDs is deleted, and retargeting is a recency game. The point is to get in front of people who look like they’re about to make a purchase, which means the utility of that behavior signal will degrade quickly.

So sellers beware. For all the fanfare, ID bridging is looking like just a stopgap measure, Johnson said.

“If you can’t create the new connections that would otherwise form,” he said, “and the old information about user behavior becomes less valuable to advertisers that want to retarget, then ID bridging eventually becomes less useful and there’s less willingness to buy those old ID-bridged users.”

Team PET

But it’s not like PAAPI is perfect either.

PAAPI still has a serious latency problem, which can mess with the user experience, especially on smartphones, which have less processing power than computers. Meanwhile, PAAPI interest groups expire after a maximum of 30 days, which makes it useless for reengaging lapsed users beyond that time frame.

Not to mention the CMA is still investigating potential competition concerns related to the planned cookie user choice mechanism for Chrome, which Google announced at the same time as its about-face on cookie deprecation.

But the purpose of this research isn’t to be rah-rah about the Privacy Sandbox, PAAPI or any other alternative targeting solution, Johnson said. The point is that privacy-enhanced targeting can be as effective as cookie-based targeting, with Privacy Sandbox as just one example.

“We’re not here to say which replacement is best – we’re neutral observers,” Kobayashi said. “We’re interested in technologies in general that can alleviate the impact that blocking third-party cookies can have.”

It’s worth noting, though, that this research focuses on how PAAPI impacts advertisers, not sellers. The CMA is looking into whether the Privacy Sandbox places a disproportionate burden on small publishers, which have fewer resources to allocate toward testing, to say nothing of the potentially dramatic negative impact cookie deprecation would have on their Chrome programmatic revenue.

On that note, Kobayashi and Johnson recently wrapped a study, which they plan to write up and publish soon, that found a relatively small effect on publisher revenue, which they mostly attribute to low adoption of the Sandbox APIs.

“If Google got rid of cookies tomorrow, advertiser adoption would increase, and that would fall to publishers,” Johnson said, who himself just published yet another study, this one examining Privacy Sandbox adoption trends in partnership with Sincera.

“But if nobody uses Privacy Sandbox,” he said, “the effect will be zero relative to the cookieless baseline.”

You can download the full PAAPI paper here: “Privacy-Enhanced versus Traditional Retargeting: Ad Effectiveness in an Industry-Wide Field Experiment.” And shoutout to Zhengrong Gu, a marketing lecturer at BU Questrom who co-authored the study with Kobayashi and Johnson.