The difference between UGC (user-generated content) and regular brand-generated content, no matter how clever, poignant or seemingly genuine, is the difference between a friend’s recommendation and an ad for a restaurant. Who would you trust more?

The difference between UGC (user-generated content) and regular brand-generated content, no matter how clever, poignant or seemingly genuine, is the difference between a friend’s recommendation and an ad for a restaurant. Who would you trust more?

According to Crowdtap, UGC is 35% more memorable – and 50% more trusted – than other forms of media.

Dave Scott, CMO of social depth platform LiveFyre, calls it the “Yelpification of brands.”

“No matter what a brand says, no matter how much advertising a brand does, the people talking about your brand on social media have more sway over it than the advertiser does,” Scott said.

National Geographic has experienced that phenomenon firsthand.

The content on National Geographic’s main website, a standard mix of articles, images and video, garners around 5,000 comments from readers each month. The content on Your Shot, Nat Geo’s active community for user-submitted photography, sees roughly 150,000 comments a month – and 3.5 million favorites.

“It’s an extremely active and engaged audience,” said Norman Gorcys, VP of product management at the National Geographic Society.

For Nat Geo, the main challenge around leveraging UGC is curation. There’s an ocean of UGC out there – and there’s also a lot of effluent. Just because a piece of content is user-generated doesn’t make it useful to a brand by default.

It’s about finding the signals in the noise, said Gorcys.

“You can’t just go out there and grab anyone who’s talking about #climatechange, for example, because there’s no telling what you’d get in that sea of information,” Gorcys said. “When it comes to UGC, we’re looking for the best stuff, the stuff that enhances a story – the stuff that engages.”

But it’s not just engagement for engagement’s sake – time is revenue.

“Our strategy is to use user-generated content to encourage community and get people more engaged,” Gorcys said. “The more engaged they are the more time they spend with us, and the more time they spend, the more ads they see. That’s how we’re monetizing right now.”

Behind the scenes, Nat Geo has been tapping into a cloud-based social curation solution from LiveFyre to power social engagement within its community. The platform, which exited beta on Tuesday, allows brands and publishers to automatically collect, categorize and store social content within a social library, a sort of dynamically updating archive.

LiveFyre also handles the rights management, reaching out to users directly for consent to leverage their images and other social content. [Permission is important. Crocs recently got into hot water for using an Instagram photo of a 4-year-old girl wearing a pair of the company’s rubber sandals in a gallery of UGC photos on its website without asking for the OK first.]

From there, brands can use the culled tweets, Instagram posts and Facebook pics in future marketing campaigns or they can display the content on their owned and operated properties through LiveFyre curation apps, like media walls, real-time feeds or galleries.

“We’re trying to help brands discover all of the interesting conversations people are having about them on social media that they don’t even how are happening,” Scott said.

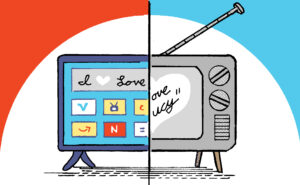

Of which there’s quite a lot – especially images. According to Mary Meeker’s 2014 Internet trend report, 1.8 billion photos are shared via social media every day, a large number of which are untagged and therefore hard to discover.

“Social media is moving increasingly toward the visual,” said David Rose, CEO of Ditto Labs, a “visual listening” startup founded out of MIT that uses image recognition technology to identify brands and products (aka objects) and context (aka scenes) in cases when there is no textual information or branded hashtag to search for.

“Social media is moving increasingly toward the visual,” said David Rose, CEO of Ditto Labs, a “visual listening” startup founded out of MIT that uses image recognition technology to identify brands and products (aka objects) and context (aka scenes) in cases when there is no textual information or branded hashtag to search for.

An image taken at a bar and shared on Twitter showing friends enjoying a round of Budweiser isn’t necessarily conveniently appended with #Budweiser or @Budweiser, but it’s still something a brand would want to know about.

According to Ophir Tanz, founder and CEO of in-image ad company GumGum, there is no text-based brand callout in around 80% of cases.

GumGum launched a platform in August called Mantii that scans social media for brand-relevant messages and gathers related demographic information.

“It’s almost even irresponsible not to know what people are posting because there is so much communication happening, especially coming from millennials and Instagram users,” Tanz said.

For its part, Ditto’s algorithm can spot thousands of different untagged objects – “A car, a bike, a tree, a Chihuahua, guacamole, a Michael Kors bag,” Rose quipped – and place them within a growing family of around 600 scenes, whether that be a wedding or a ballgame or restaurant or a movie theater. The algorithm can also discriminate reversed mirror images, as well as obscured logos, say an unzipped sweatshirt that splits the logo in two. [Ditto is even selling its data to government agencies looking for ISIS references in social images.]

At present, most of Ditto’s clients, which include P&G, Kraft and General Mills, use its service as a social listening tool to determine an ad campaign’s influence or to see how their products are being used and talked about on social media.

But Rose envisions brands using the tool to create audiences or directly engage with individual people based on the photos they’ve posted – segmentation that goes beyond the like. Few people will likely remember having reflexively liked a turkey stuffing brand, for example, but most people will remember the photo they posted of the family gathered around the table for Thanksgiving dinner.

“Sure, brands can look at the number of people following them on social media,” Rose said. “But if they’re actually trying to aggregate an audience based on likes or follows and not affinity, that’s always just going to be a fail.”