“The Sell Sider” is a column written by the sell side of the digital media community.

“The Sell Sider” is a column written by the sell side of the digital media community.

Today’s column is written by Chris Kane, founder at Jounce Media.

AppNexus CEO Brian O’Kelly recently published an authoritative breakdown of the multiple routes by which publishers unintentionally leak data into the hands of bad actors.

In the post, he compares data to radioactive fallout: “It’s hazardous; invisible; expensive; dangerous.”

There’s another thing about data that makes it a lot like radioactive material – it has a half-life.

Radioactive half-life describes the amount of time it takes for a piece of radioactive material to emit 50% of its total radiation. Some radioactive materials decay extremely quickly – polonium’s half-life, for example, is less than a hundredth of a second. Other radioactive materials are slow burners – uranium’s half-life is almost 5 billion years.

Data also has a half-life. Some pieces of marketing data are ephemeral, providing useful consumer intelligence for very short periods of time. Information about a consumer’s desire to watch a specific movie might be useful for just a few moments. During that short decision-making period, ads promoting new releases might prove highly impactful, but once the consumer’s movie selection is made, his or her intent has decayed and the data’s value disappears.

Other pieces of marketing data live nearly forever. Information about a consumer’s occupation or political affiliation might remain relevant to marketers for years, powering thousands of ad-buying decisions.

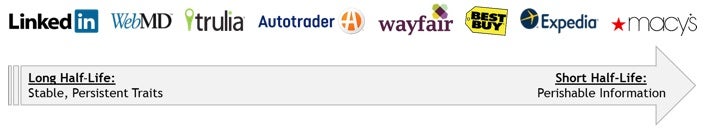

Publishers can think about their data assets in terms of data half-life. Media companies whose audiences are making low-consideration purchase decisions might have a data half-life of just a few hours. By contrast, media companies whose audiences exhibit stable, persistent lifestyle traits may have a data half-life of many years.

Even within a single category like travel, data half-lives can vary from many months (planning a honeymoon on TripAdvisor) to just a few hours (comparing airline fares on Kayak).

Data half-life says a lot about the degree to which publishers can tolerate a culture of experimentation. Publishers with fast-burning data can test emerging programmatic sales channels, allow new third-party trackers on their pages and even explore direct data-licensing agreements without fear of long-term consequences. As experiments are determined to be failures, they can be decommissioned, and any leaked data will quickly decay and become useless to marketers.

Even within media companies whose data assets typically have long half-lives, there may be pockets of fast-burning data. WebMD might choose to launch new data products on its flu season page before deploying them sitewide. Best Buy might approve third-party trackers on its video game section before expanding to the home appliance section. Trulia might test a new header bidding partner on its rental listings before moving to sales listings.

Publishers, separate your fast-burning data from your slow-burning data. Unleash your most innovative teams on data with a short half-life. Let them experiment, make mistakes and develop best practices on your fastest-burning data.

But protect your slow-burning data. Leaking data with a long half-life is a mistake from which you might never recover.

Follow Jounce Media (@jouncemedia) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.