“The Sell Sider” is a column written for the sell side of the digital media community.

“The Sell Sider” is a column written for the sell side of the digital media community.

Today’s column is written by Ari Paparo, CEO at Beeswax.

It may sound like the latest in young adult fiction, but this mystery is not dramatic or amusing, nor will it make your teenager ask you for money for the movies.

The mystery is this: In the supposedly super-efficient world of RTB, why would publishers continue to waterfall their demand sources?

Spoiler alert: This column will not actually answer the question. I merely posit possible explanations, which you will have to wait to see if the writer can tie together in an as-of-yet unscheduled Episode 2.

First, let’s start with some economics. As should be familiar to anyone who has anxiously waited for an airline upgrade, there’s a big difference in price between coach and business class, and it’s not easy to switch between the two. The economic theory behind this is that, as a seller, you can maximize your profit by touching different consumers on different portions of the demand curve.

Differential pricing maximizes yield on a demand curve

Before the exchanges, most publishers executed demand segmentation through a waterfall of tags. Tags from various ad networks would load only after someone else had passed on the impression. The lower you were on the waterfall, the fewer premium impressions you had access to, which was a form of quality discrimination. If you don’t believe this matters, consider the difference in ad impression value between the first page of a slideshow and the last one.

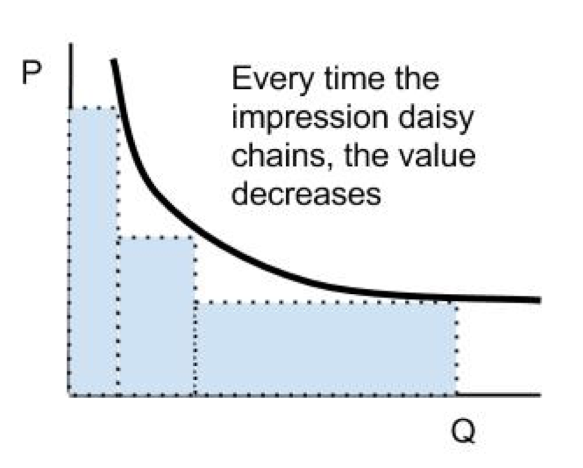

Differential pricing using an old-fashioned waterfall/daisy chain

Fast forward to today’s world, where every impression can be simultaneously auctioned to every potential demand source in real time, with business rules customized to maximize revenue. This should allow publishers to maximize yield, not just on two points of the demand curve, but theoretically on every point.

Diagram: How RTB should be the perfect solution to maximizing yield

So what do smart publishers actually do? They waterfall, or “daisy chain,” supply-side platforms (SSP). They send an impression to their preferred SSP with a relatively high floor price, then if the impression doesn’t clear, they redirect it to a second SSP with a slightly lower floor price, and repeat the process until AdSense clears the impression at pennies. This is essentially differentiating demand based entirely on the buyers being unaware that they could buy the same inventory cheaper. It’s as if you were able to repeatedly reload the American Airlines site and get cheaper prices for the same seat. When you ask publishers why they do it, they say, “Because it works.”

This is the ugliest secret in programmatic. I’ve personally verified it with more than a few top ad ops folks.

Any economist could tell you that this is a bad idea. But the ad ops folks insist that it works. So let’s trust them and try to answer the waterfall mystery: Why does it work?

Hypothesis No. 1: Different SSPs Have Different Demand Density

This seems like the obvious answer, but upon closer inspection, it doesn’t make sense. The top 80% of demand comes from a handful of bidders that integrate with everyone. Further, if one SSP had so much more demand than the others, it would always be the first in the daisy chain and gain significant share. But publishers insist they must move the order around over time and the SSP market remains a fairly stable oligopoly.

Conclusion: Unlikely.

Hypothesis No. 2: SSP Tools Produce Different Yields On The Same Inventory

The SSPs do have varied tools to manage yield. But once again, if one is dramatically and consistently better than the others, the market would reach equilibrium with the leader on top for most clients. This is not the case.

Conclusion: True, but unlikely to be the cause of the waterfall.

Hypothesis No. 3: Buyer Tools Differentiate By Supply Source

Do bidders price the same inventory differently if it comes from different supply sources? If so, this would cause some unpredictability in determining optimal auction settings, and switching between SSPs would be a crude way of generating incremental yield. But this could also cause reduced yield, since the combination of auctioneer, inventory and buyer would be hard to predict.

Conclusion: Possible, but hard to test.

Hypothesis No. 4: The Buyers (And Their Tools) Are Dumb

What if most buyers just don’t realize they can get the same impressions at lower prices and are instead consistently buying impressions for higher prices than they would ultimately clear for?

This would explain both the need for multiple auctions – to fool buyers into thinking they are distinct impressions – and the need to switch the order of the waterfall – to throw off the demand-side platforms once they have reached an optimized state.

Conclusion: This is a clear contender!

Hypothesis No. 5: Ad Ops Teams Like Messing With Things

What if yield is just going up because someone is paying close attention and tweaking settings a lot? See the Hawthorne effect.

Conclusion: Possible, but don’t tell ad ops.

I’m interested in hearing your thoughts. In a future article I’ll work through the strategic implications of this situation.

Follow Ari Paparo (@aripap), Beeswax (@BeeswaxIO) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.