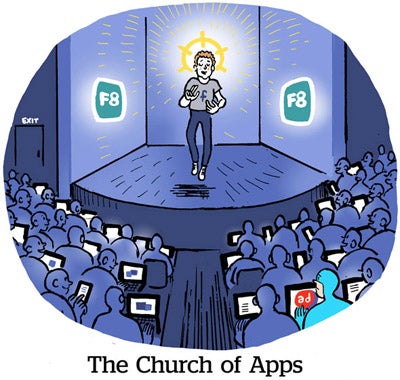

Mobile app install ads are still a multibillion-dollar business for Facebook. But is Facebook taking too much credit?

It’s hard to say, because Facebook is what’s known as a self-attributing network, i.e., a walled garden.

A self-attributing network is just what it sounds like: a platform that, usually because of its scale, has the power to do its own attribution calculations without the input of third-party tracking providers. Facebook, Google and Twitter all fall into this category.

Although Facebook does run a mobile measurement partner (MMP) program, members aren’t privy to how Facebook decides what to take credit for.

“Obviously, Facebook is not trying to dupe marketers, but the data moves in the wrong direction here,” said Chris Kane, founder of programmatic consultancy Jounce Media. “App install data is being sent to Facebook for Facebook to do the measurement when what should be happening is for Facebook to send that data to the marketer.”

Facebook’s default attribution windows – 28 days for post-click and 24 hours for post-view – allow Facebook to request credit for conversions that take place nearly a month after the initial ad click and a full day after someone saw an ad but didn’t click.

Last, despite Facebook’s enormous scale – 2.1 billion monthly active users and 1.32 billion daily active users as of June – it doesn’t see everything.

Facebook knows when users view or click on an ad, like a Facebook page, make a purchase or leave a comment on a post as they browse and move down the funnel, but it can’t know if what ultimately drove the conversion was an ad exposure on another platform like Snapchat or Spotify.

“It boils down to two main problems: grading your own homework and proving incrementality,” Kane said. “Is a promoted Facebook post you saw three weeks ago actively influencing your decision to install a game? Maybe, but I’m skeptical.”

Long Window

Although most app installs happen almost immediately after an ad click, Facebook reserves the right to claim credit for conversions that happen within 28 days.

In theory, ad networks that don’t self-attribute could set nearly unlimited attribution windows since there isn’t an official standard in place to determine their length, but the vast majority attribution vendors abide by a seven-day attribution window for clicks, although some argue that’s even too long.

A longer window increases the likelihood an ad will be assigned some value – and the likelihood that a publisher will end up taking credit for organic installs that would’ve happened without paid media.

Toby Roessingh, a quantitative researcher in Facebook’s Marketing Science division and manager of the attribution partner program, acknowledged that a long window can sometimes allow for “coincidences.”

“The longer the window, the more room you allow for coincidence,” Roessingh said. “But the fact is we have millions of advertisers buying ads on Facebook and it’s hard to make a blanket statement about what length of window is appropriate across the whole landscape. This is why advertisers should work to understand how their customers respond to their advertising and assess their approach to attribution against experiments.”

But 28 days makes Facebook difficult to measure in relation to other media, said Maor Sadra, managing director and CRO of mobile marketing platform AppLift.

“Facebook represents the majority of spend for many developers and I’d go so far as to say that is because of the attribution mechanics,” Sadra said. “How can you benchmark Facebook with a 28-day default?”

Facebook says leaving the window open wide makes sense because it gives advertisers an idea of the scope of activity during and after a campaign, Roessingh said.

A 28-day window for clicks and 24-hour window for post-view is “the data we’re willing to provide, that we feel can account for all of the direct responses to ads. We recognize that advertises won’t always give us the credit,” he said.

Facebook’s window is a catch-all, which is why it’s so important for advertisers to run tests to see which platforms should be part of their mix, said David Lee, CEO and founder of Shakr, a video ad creator and Facebook marketing partner.

Facebook’s window is a catch-all, which is why it’s so important for advertisers to run tests to see which platforms should be part of their mix, said David Lee, CEO and founder of Shakr, a video ad creator and Facebook marketing partner.

“Gaming companies in particular should tighten up their windows to just a day or two, and that is something Facebook provides,” Lee said. “It would help clean up their data very quickly.”

It’s worth calling out, however, that advertisers can opt to only pay for conversions that takes place within shorter windows – one day or seven days – and Facebook will optimize for clicks and views based on their choice. Advertisers aren’t billed for conversions that take place within a longer window if they opt for a shorter one.

Although few advertisers take advantage, they do have the ability to manually shorten their Facebook click window on a campaign-by-campaign basis. They can also instruct their attribution partner to only give credit within a particular timeframe, including to Facebook. While Facebook might give itself credit for an install on day eight, if an ad served by AppLovin led to an install that occurred on day seven, AppLovin would get the credit.

That’s why it’s so difficult to create standards for the mobile app attribution space, despite the need. Different windows make sense for different advertisers and different products.

But the core issue actually has less to do with the length of an attribution window, and more to do with Facebook’s status as a self-attributing network.

Black Box

Most publishers share all of their impression and click data with their mobile attribution partners, who use that information to claim credit.

In Facebook’s case, it’s the other way around.

MMPs send campaign outcome data to Facebook, which compares that data with its own ad-serving data. If Facebook finds an exposure on its platform that occurred prior to the conversion, Facebook alerts its MMP that it’s making a credit claim.

This is how it works in practice: When someone downloads an app, an attribution provider like AppsFlyer, Adjust, Kochava or Singular (all Facebook MMPs) receives exposure data from the ad network claiming credit for serving the ad that led to the conversion along with a time stamp and the device ID.

The MMP sends the info related to that app install to Facebook, which compares it to its own exposure data. Facebook then determines whether that same person clicked on or viewed an ad on Facebook before or after the engagement being reported by the ad network.

Then it’s up to the MMP to evaluate the two claims for credit and decide which one is stronger based on the type of engagement – a click trumps a view – and when it happened: The more recent the engagement, the sturdier the claim. A classic last-click attribution model.

“If we make an attribution claim, what we’re simply saying is that we think we played a part in that, so we want credit for it,” said Roessingh, noting that Facebook’s mobile measurement partners “play an important role in arbitrating those claims claims across publishers.”

The problem, said Kane, is that MMPs are not able to independently verify Facebook’s claim.

There are also discrepancies between MMPs, Sadra said, noting that he’s spoken with some attribution providers that have admitted to between a 5% and 50% disparity between what they report and what Facebook reports.

“There’s no doubting that Facebook has the reach and that it’s a tremendous platform to run a campaign on,” Sadra said. “But I am doubting that the performance being reported is as great as Facebook says.”

But visibility into Facebook’s app-install attribution system will remain nil unless buyers band together to throw their weight around a la P&G’s Marc Pritchard.

“It’s the advertisers that need to put pressure on the supply side and the attribution side,” AppLift’s Sadra said. “If enough advertisers, the ones who hold the budget, don’t accept this, they could push Facebook and the industry at large to set a standard.”

Story updated 12:21 p.m. ET to reflect a reference to Google and Twitter as self-attributing networks and a clarification on billing as it relates to credit claims.